The OCC has released Passport to Prosperity, documenting its recommendations on immigration reform. The recommendations aim to increase Canada’s global competitiveness and close the skills gap by making Canada and Ontario more receptive and flexible when it comes to welcoming skilled and talented immigrants. Read more below.

PASSPORT TO PROSPERITY

PASSPORT TO PROSPERITY

Ontario’s Priorities for Immigration Reform

CONTENTS

A Letter from the President & CEO

Summary of Recommendations

Introduction

Ontario’s Immigration Challenge

Recommendations

Address Barriers to Opportunity within the Selection System

Prioritize the Attraction and Retention of International Students

Improve the Coordination of Labour Market Integration and Settlement Services

Conclusion

A LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CEO

In the global economy, Canada’s diversity is our greatest competitive advantage. Together, we represent more than 200 ethnic origins and speak more than 200 languages. One out of five people in Canada’s population is foreign-born. Over 53 percent of these individuals have chosen to settle in Ontario (Statistics Canada, 2015a).

As the province that receives the most immigrants in the federation, Ontario is particularly invested in achieving reforms designed to advance the prosperity of both new market entrants and the economy. Accordingly, this report presents Ontario’s priorities for immigration reform.

In addition to possessing the talents critical to filling our existing skills gap, immigrants to Ontario are equipped with valuable language abilities as well as foreign business networks and market knowledge that have the potential to greatly contribute to the global competitiveness of Ontario businesses.

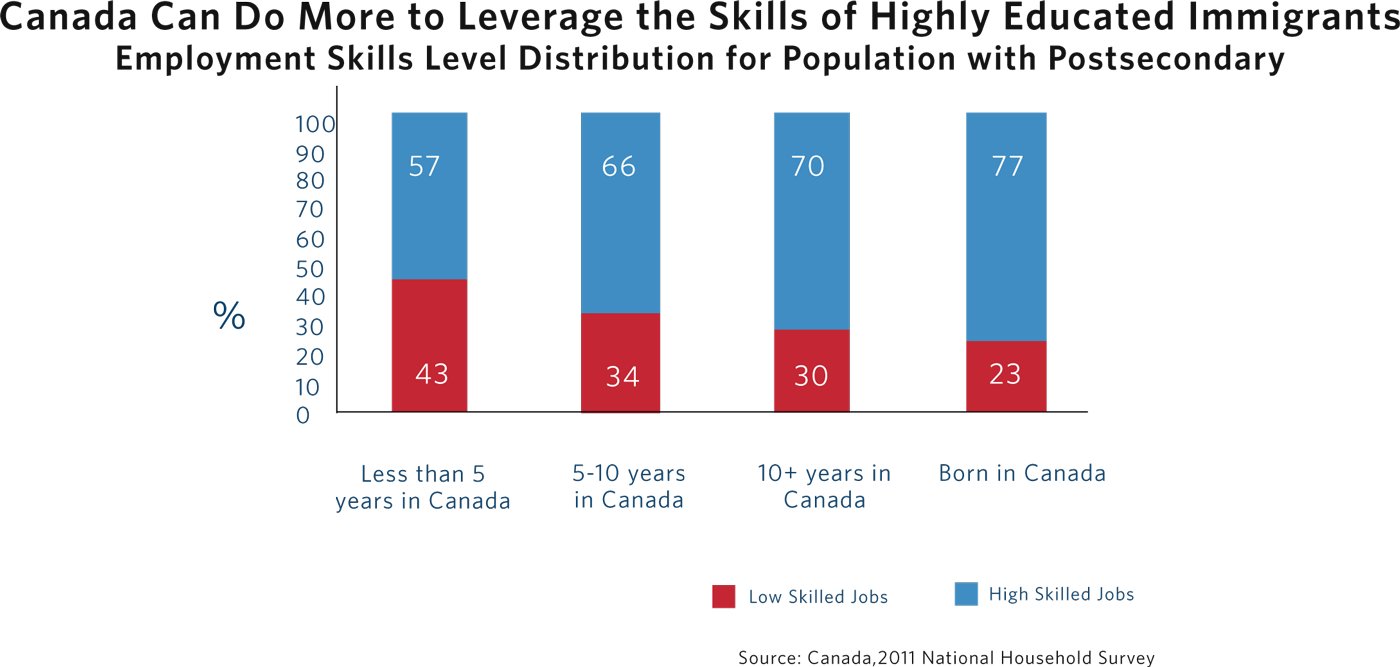

That said, we should be better at leveraging the skills and global connections of new Ontarians. Immigrants to Ontario experience poor labour market outcomes relative to their Canadian-born peers. Only 57 percent of recently arrived, postsecondary educated immigrants to Ontario are actually working in high-skill jobs. In comparison, 77 percent of people born in Canada with post-secondary education are working in high-skill jobs. (Statistics Canada, 2011).

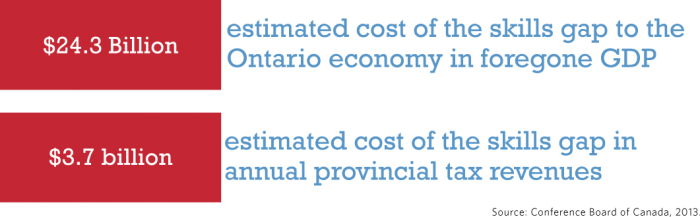

At the same time, many key Ontario sectors are facing skills shortages. The Conference Board of Canada estimates that the skills gap costs the Ontario economy up to $24.3 billion in foregone GDP and $3.7 billion in provincial tax revenues annually (Conference Board of Canada, 2013). Demographic trends suggest that over the next 25 years, immigration will be a main source of future labour market growth (Kustec, 2012). It is critical that Ontario continues to attract and retain highly-skilled immigrants to meet our labour market needs.

Clearly, there is an opportunity for the government and employers to work together to address these challenges and, in the process, develop an immigration system that is more responsive to labour market demand.

In this report, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce presents a series of recommendations designed to reduce Ontario’s costly skills gap and improve immigrant labour market outcomes in the province. These recommendations have been developed through extensive consultation with our membership. By taking these actions to reform the selection system and committing to enhanced cooperation with the business community and the provincial government, Canada will position itself to better leverage the global connections of Ontario’s workforce.

Sincerely,

Allan O’Dette, President & CEO,

Ontario Chamber of Commerce

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

To improve the labour market outcomes of immigrants and to ensure that Ontario businesses are able to effectively

leverage the talents and global connections of its workforce, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce recommends that

the Government of Canada take the following actions:

- Address Barriers to Opportunity within the Selection System

- Enhance the flexibility of Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) allocations.

- Remove the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) requirement from the Express Entry system.

- Work with the Government of Ontario, chambers of commerce and other sector organizations to increase awareness of the Express Entry system.

- Prioritize the Attraction and Retention of International Students

- Revise the Canadian Experience Class to award additional points to graduates of Canadian colleges

and universities. - Benchmark study permit processing times against comparable systems.

- Maintain the Federal International Education Strategy.

- Revise the Canadian Experience Class to award additional points to graduates of Canadian colleges

- Improve the Coordination of Labour Market Integration and Settlement Services

- Renew the Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement (COIA).

- Leverage the Municipal Immigration Information Online Program to develop a coordinated outreach strategy to retain immigrants in rural and northern communities.

- Re-open immigration offices throughout the province to provide in-person services to refugees and immigrants.

INTRODUCTION

Labour mobility and access to highly skilled talent are among the top priorities of the Ontario Chamber of Commerce’s (OCC’s) 60,000 members. We recognize that there is an opportunity to advance both of these priorities through reform to the existing immigration system.

The 2014 OCC report Think Fast: Ontario Employer Perspectives on Immigration Reform and the Expression of Interest System considered the potential of the Express Entry system to refocus the immigration system on talent and human capital. The purpose of this report is to understand, one year after the release of the system, how far we’ve come to realizing that objective.

Over the past six months, the OCC has conducted extensive consultations with our members and the broader business community on their experience with the immigration system as employers. These experiences, supported by data collected by the OCC through a series of membership surveys, have informed the recommendations in this report.

While the Express Entry system was a step in the right direction, barriers to opportunity for both immigrants and employers remain. The recommendations presented in this report have been designed to address those barriers as well as to improve the labour market outcomes of immigrants in Ontario, recognizing that training the existing workforce should be considered a core component of the province’s labour force strategy.

In this report, we first describe Ontario’s labour market challenges. We then present a series of recommendations designed to address these challenges within the following priority areas: addressing barriers to opportunity within the selection system, prioritizing the attraction and retention of international students, and improving the coordination of labour market integration and settlement services.

Throughout our consultations, it became apparent that Ontario employers are highly invested in working with government to build an immigration system that is more responsive to our labour market demand, improves the labour market outcomes of immigrants, and contributes to the competitiveness of Canadian business.

ONTARIO’S IMMIGRATION CHALLENGES

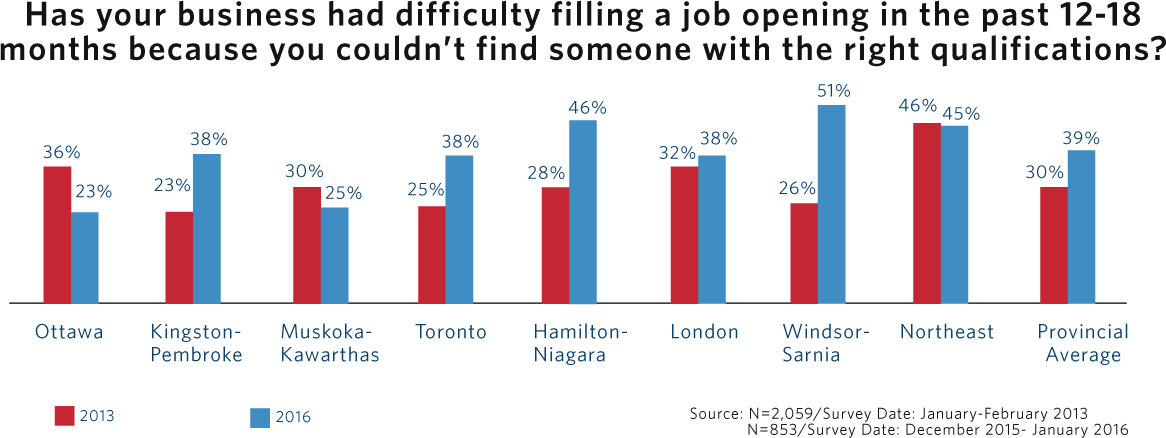

The skills gap in Ontario is worsening. In 2014, OCC survey data revealed that 30 percent of businesses here had difficulty filling a job opening over the last 12 to 18 months because they could not find someone with the right qualifications (OCC, 2013). In 2016, this number increased to 39 percent* (OCC, 2016).

In some regions, this trend has been much more pronounced. In 2014, 28 percent of respondents in the Hamilton-Niagara region indicated that they had had difficulty filling a job opening compared to 52 percent of respondents in that region in 2016 (OCC,2016).

As much of the province’s future net labour growth will come from immigration, it is critical that we ensure that Ontario businesses are well positioned to attract and retain skilled international talent to fill the skills gap that costs the Ontario economy up to $24.3 billion in foregone GDP and $3.7 billion in provincial tax revenues annually (Conference Board of Canada, 2013).

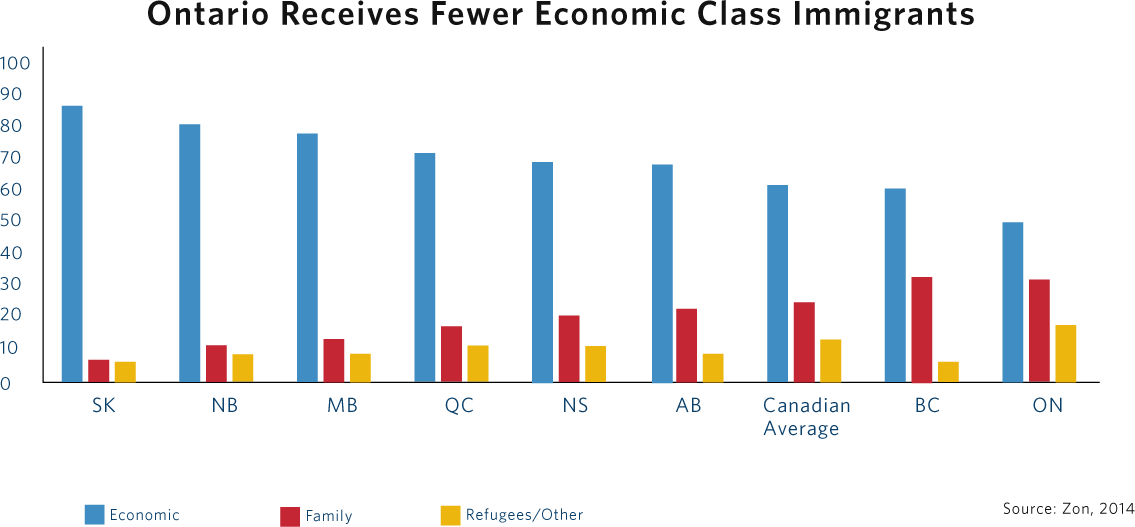

The evidence suggests, however, that Ontario is attracting fewer and fewer economic immigrants positioned to address the skills gap. The number of economic immigrants to Ontario declined by 46 percent from 95,091 in 2001 to 50,948 in 2014 (IRCC, 2015).

In comparison to all other provinces, Ontario also receives the lowest proportion of economic immigrants and the highest proportion of immigrants through the family reunification and refugee, protected persons, humanitarian, and other categories. As a result, Ontario is adding fewer new immigrants to its workforce than other provinces (Zon, 2014).

At the same time, labour market outcomes for immigrants across Canada are poor: a larger share of highly skilled immigrants is employed in low-skilled occupations and the wage gap between Canadian-born workers and university-educated immigrants landed 10 years or less has increased. Recent data reported by Statistics Canada indicates that very recent immigrants aged 25 to 54 with a university degree earned 67 percent of the wages of their Canadian-born counterparts (Statistics Canada, 2015a).

In 2015, the federal government introduced the Express Entry system to address these challenges. In order for employers to use the Express Entry system as a talent recruitment tool, they must first demonstrate that they have made every effort to try to fill vacant job opportunities with a Canadian or permanent resident by completing a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA). A positive LMIA will demonstrate that no Canadian worker is available to fill the job vacancy in question. It is at this stage that employers are granted access to the Express Entry talent pool via an online portal (IRCC, 2015d)

The system was designed to mitigate processing times while improving the economic outcomes of immigrants by ensuring that new market entrants to Canada possess the skills and qualifications demanded by Canadian employers (IRCC, 2015b). However, multiple employers that we consulted indicated that certain features of the Express Entry system are compromising their ability to recruit international talent. In addition, many employers also demonstrated a lack of awareness about the Express Entry system as a whole.

These findings were supported by recent survey data collected by the OCC which reveals that less than seven percent of SMEs in Ontario had used the immigration system for hiring purposes.7

Ontario’s immigration challenges suggest that more work needs to be done. The recommendations presented in this report have been designed to address these barriers to opportunity for both Ontario employers and international talent within the immigration selection system.

ADDRESS BARRIERS TO OPPORTUNITY WITHIN THE SELECTION SYSTEM

ADDRESS BARRIERS TO OPPORTUNITY WITHIN THE SELECTION SYSTEM

Address Barriers to Opportunity within the Selection System

- Enhance the flexibility of Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) allocations.

- Remove the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) requirement from the Express Entry system.

- Work with the Government of Ontario, chambers of commerce and other sector organizations to increase awareness of the Express Entry system.

Each year, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) releases an Immigration Levels Plan that provides a target for the number of people the government expects to admit as permanent residents each year within each of the three primary immigration categories: Economic; Family Reunification; and Refugees, Protected Persons, Humanitarian, and Other (Government of Canada, 2016).

The primary function of Canada’s economic immigration system is to recruit people with the skills and qualifications required to address labour market gaps. In the recently released 2016 Immigration Levels Plan, the IRCC established a target range of 151,200 – 162,400 people to be admitted to Canada through the economic category (Government of Canada, 2016). In comparison, the 2015 target range for economic class immigrants was 172,100 to 186,700 (IRCC, 2014).

We commend the federal government for its commitment to temporarily adjust the immigrations levels to accommodate a greater number of refugees in light of the Syrian crisis (Berthiaume, 2016). Given the importance of economic immigrants to our, economy, however, we urge the government to reinstate the economic category immigration target as soon as possible and by no later than 2017/18.

In addition to the Express Entry system described earlier, the federal and provincial governments offer a number of programs that allow employers to tap into the immigration system to meet their labour market needs. In particular, the Provincial Nominee Programs (PNP), jointly administered by provinces and territories with IRCC, bring in large numbers of economic immigrants to Canada (IRCC, 2015f).

The following section of the report identifies certain features of both the Express Entry system and the PNP that compromise employers’ ability to recruit international talent through the immigration system, thereby lessening the number of opportunities available to international talent in Ontario.

The recommendations presented in this section of the report have been designed to address these barriers to opportunities for both Ontario employers and international talent within the immigration selection system.

Recommendation 1.i: Enhance the flexibility of Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) allocations.

All provinces/territories, with the exception of Quebec and Nunavut, nominate immigrants through Provincial Nominee Programs (PNP) (IRCC, 2015f). These programs are jointly administered by PTs and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and are facilitated by way of Federal/Provincial agreements. The Ontario’s nominee program, known as the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program (OINP), offers employers the opportunity to recruit and retain highly skilled foreign workers and international students (MCIIT, 2015a).

Each year, IRCC provides a nominee allocation to provinces and territories. The provincial allocation is divided between base allocation and enhanced allocations. Immigrants nominated through the enhanced allocation stream must qualify for one of the federal economic streams administered through Express Entry and be eligible for selection in the EE pool. Immigrants nominated through the base allocation stream must meet requirements established by the province through their own Provincial Nominee streams.

In 2015, Ontario’s total nominee allocation was 5,200. Of these 5,200 nominations, 2,500 were allocated for use through base streams and 2,700 were allocated to be used through the enhanced or Express Entry streams (MCIIT, 2015b).

In order to be eligible under the base allocation stream in Ontario, an immigration candidate must have a permanent, full-time job offer in a highly skilled occupation that meets the prevailing wage levels in Ontario for that occupation. The foreign worker must have two years of relevant work experience in the last five years (MCIIT, 2015c). International students are also eligible to apply for permanent residence through the OINP base allocation stream.

Given that the province has the ability to adjust the requirements of the base allocation stream to meet the particular demands of its labour market, we recognize that the expansion of the base rather than enhanced allocation would be an optimal tool for creating greater opportunities for international talent to settle in Ontario and ensuring that the OINP remains responsive to the labour needs of Ontario employers.

The expansion of the PNP base allocations would increase Ontario’s ability to respond to its unique labour market needs and maximize the economic benefits of immigration. For this reason, we recommend that the Government of Canada increase the number of PNP base allocations in Ontario or introduce greater flexibility in the overall allocation to Ontario.

Recommendation 1.ii: Remove the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) requirement from the Express Entry system.

The Express Entry system requires that employers obtain a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) before hiring a foreign worker. A positive LMIA will show that there is a need for a foreign worker to fill the job and that no Canadian worker is available to do the job (IRCC, 2015d).

As discussed in a recent Canadian Chamber of Commerce report, the LMIA fails to recognize that employers generally tend to consider Canadians first for the job due to the fact that it is significantly cheaper and easier to hire a Canadian citizen than it is to hire international talent (CCC, 2016). The government should recognize that if employers are attempting to use the Express Entry system it is because they have exhausted their local talent pool.

Perhaps of greater concern, however, are the punitive fines associated with the LMIA which deter employers from utilizing the Express Entry system. Employers found noncompliant with program requirements could be subject to financial penalties ranging from $500 to $100,000 per violation up to $1 million in a one-year period (CIC, 2015). The threat of such punitive fines deters employers, particularly small to medium sized business owners, from using the program; they simply can’t afford the time and money associated with employing legal counsel to help them navigate the process.

Evidently, the fewer employers that make use of the Express Entry system, the fewer opportunities available for international talent to relocate to Canada. In order to maximize the economic contribution and labour market outcomes of immigrants, we recommend that the federal government remove the LMIA requirement from the Express Entry system.

Recommendation 1.iii: Work with the Government of Ontario, chambers of commerce and other sector organizations to increase awareness of the Express Entry system.

The Express Entry system represents a significant opportunity for employers to recruit international talent to permanently fill 85 percent of vacant positions within six months (CIC, 2015). Despite the significant costs associated with leaving a position unfilled, too few employers are using the Express Entry system to obtain the talent that they desperately need.

According to our consultations, the largest contributing factor to this dilemma is a lack of awareness and understanding of Express Entry within the business community. In many instances, employers have assumed that the application process would take too long. Instead, they hired international talent through the Temporary Foreign Worker program.

This behaviour is problematic for a few reasons. First, the employer’s long-term skills gap remains unresolved. Second, employers find themselves investing in the training and development of an employee that, by virtue of being a ‘temporary foreign worker’, will most likely be required to return to his or her home country after just a few short years. Third, the misdirection of applications from the Express Entry system to the TFW compromises the global competitiveness of the Canadian immigration system by contributing to the administrative burden and sluggish processing times associated with the recruitment of international talent.

The federal government has developed the Employer Liaison Network (ELN) in response to these challenges. The ELN is designed to help employers learn about the Express Entry system and connect with skilled workers oversees (IRCC, 2016b). Through our consultations, however, it became evident that very few employers are aware of the ELN.

We recommend that the federal government work with local chambers of commerce and boards of trade, as well as other sector organizations, to address common misconceptions of the Express Entry system within the Ontario business community. By leveraging the connections of these organizations to employers as well as existing programs such as the ELN, the government can increase awareness of, and potentially increase interest in, the Express Entry system, thereby ensuring that the program realizes its objective of attracting highly skilled international talent to resolve costly skills gaps.

PRIORITIZE THE ATTRACTION AND RETENTION OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS

PRIORITIZE THE ATTRACTION AND RETENTION OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS

Prioritize the Attraction and Retention of International Students

- Revise the Canadian Experience Class to award additional points to graduates of Canadian colleges and universities.

- Benchmark study permit processing times against comparable systems.

- Renew the Federal International Education Strategy.

The economic benefits of international students studying in Canada are significant. Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada estimated that in 2010, international students spent in excess of $7.7 billion on tuition, accommodation, and discretionary spending; created over 81,000 jobs; and generated more than $445 million in government revenue (Global Affairs Canada, 2013). Further, it was estimated that international students and their family and friends contributed an additional $336 million in 2010 to the Canadian economy through spending on tourism related activities (Roslyn, Kunin and Associates, 2012).

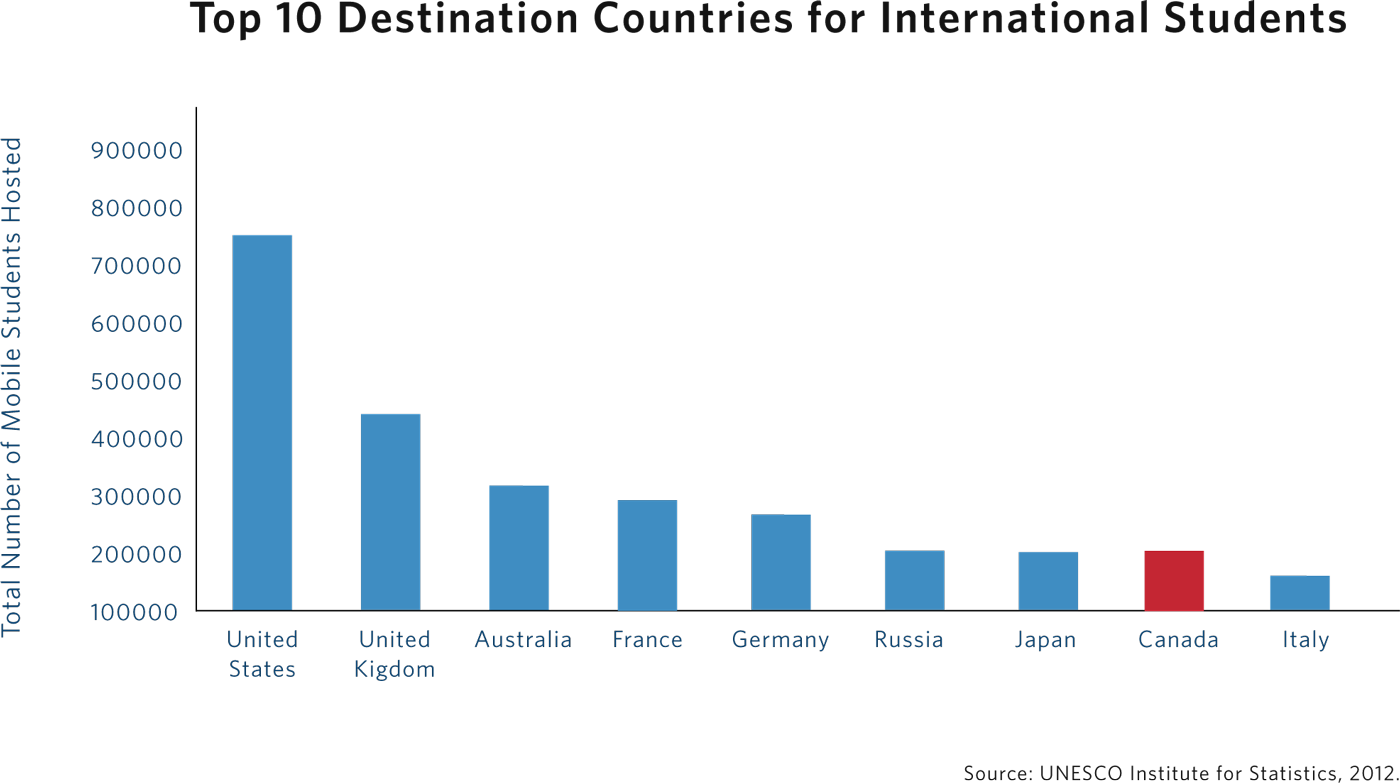

The evidence suggests, however, that Canada could do a better job of attracting retaining international students. Canada currently ranks as the 8th top destination country of international students, having attracted 135,187 or 3 percent of globally mobile students in 2012. Compared to the rest of the world, however, this is a relatively small number, as the top six destination countries hosted nearly one-half of total mobile students: the United States (hosting 19 percent of global internationally mobile students), United Kingdom (10 percent), Australia (6 percent), France (6 percent), and Germany (5 percent) and Russian Federation (three percent) (UNESCO, 2016). Canada is in a global competition to attract the best and brightest minds in the world. The challenge is twofold: first, attracting talent to Canada, and second, creating employment and permanent settlement opportunities to ensure that this talent continues to contribute to our economy.

The following recommendations have been designed improve the attraction and retention of international students.

Recommendation 2.i: Revise the Canadian Experience Class to award additional points to graduates of Canadian colleges and universities.

The Canadian Experience Class (CEC) is the fastest and simplest immigration program for international students to achieve permanent residency (Canada Visa, 2016). However, the CEC does not give any preference to immigrants who have completed their degree in Canada; an international graduate of a Canadian university has no advantage over those trained outside of Canada seeking Permanent Residency (IRCC, 2015a).

In contrast, international graduates of Australian universities are awarded through the points system associated with the Skilled Independent Visa subclass of the General Skilled Migration (GSM) system. In the GSM system, points are awarded to candidates that have graduated from an Australian institution or completed a trade qualification in Australia (Dept. of Immigration, 2016a).

We recommend that the Canadian government follow the Australian example and revise the scoring allocation in the CEC to recognize international graduates of Canadian colleges and universities. The implementation of this recommendation will contribute to Canada’s attractiveness to international students, particularly those that are interested in permanently relocating from their home country.

Recommendation 2.ii: Benchmark the processing times for study permits against comparable systems.

Processing times for study permits – official documents granted by the federal government that give applicants permission to study in Canada – vary depending on where students apply from. For example, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) estimates the processing time of a study permit from China to take six weeks, India to take four weeks, and Brazil to take eight weeks (IRCC, 2016a).

The Australian government aims to process 75 percent of student visa applications within the service standard of two to four weeks (Dept. of Immigration, 2016b). It is critical that the Canadian government adopt a comparable commitment to ensure that Canada’s processing times are globally competitive. In some instances, such as in the case of students applying from Brazil, this will involve committing to halving the processing times of student visas and will require increased capacity within IRCC.

Recommendation 2.iii: Maintain the Federal International Education Strategy

In January 2014, the federal government announced the creation of the International Education Strategy with the objective of doubling the number of international students studying in Canada from 265,377 in 2012 to 450,000 in 2022. Through the Strategy, the federal government committed $5 million per year to market Canada internationally as a ‘world class education destination’ (Simon, 2014).

In 2006, the United Kingdom launched a comparable international education strategy that is recognized as having contributed to its ability to meet its target of attracting an additional 70,000 international students to the UK in five years. In addition, evaluations of the UK strategy revealed that it resulted in improved student satisfaction and increased international institutional partnerships (Advisory Panel, 2012). Similarly, the United States promotes its educational institutions through a variety of programs, most notably EducationUSA and the ‘Study in the States Initiative’ administered by the Department of Homeland Security. The Initiative includes an interactive website that is linked to a variety of social media platforms (Advisory Panel, 2012).

It is critical that the federal government continue to invest in the pan-Canadian International Education Strategy to ensure that its marketing efforts are capable of achieving outcomes similar to those of leading jurisdictions such as the UK and the US.

In addition to including a commitment to brand the advantages of studying in Canada, the Strategy aims to contribute to the economic diplomacy and trade promotion activities by leveraging the global connections of international students, particularly those connected to countries identified as ‘emerging markets’ with high growth potential. Between 2010 and 2014, for instance, 65 percent of Ontario’s international students came from source countries identified as emerging markets.

For these reasons, we recommend that the federal government continue to invest in the International Education Strategy to advance Canada’s competitiveness as an education destination for the best and brightest students in the world.

IMPROVE THE COORDINATION OF LABOUR MARKET INTEGRATION AND SETTLEMENT SERVICES

IMPROVE THE COORDINATION OF LABOUR MARKET INTEGRATION AND SETTLEMENT SERVICES

Improve the Coordination of Labour Market Integration and Settlement Services

- Renew the Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement (COIA).

- Leverage the Municipal Immigration Information Online Program to develop a coordinated outreach strategy to retain immigrants in rural and northern communities.

- Reopen immigration offices throughout the province to provide inperson services to refugees and immigrants.

Despite the challenges identified in the preceding sections, the OINP and Express Entry systems are effective in ensuring that new market entrants to Ontario are highly skilled; 77 percent of very recent immigrants to Ontario (those arriving in the last five years) have postsecondary credentials (Gov. of Ontario, 2013).

The evidence suggests, however, that these skills are too often going to waste. A significantly larger share of very recent immigrants with postsecondary credentials, 43 percent, is employed in low-skilled occupations in comparison to 23 percent of their Canadian-born counterparts (Gov. of Ontario, 2013).

The federal and provincial governments have developed a variety of resources to improve the labour market outcomes of immigrants including the Ontario Bridge Training Program and language training in the workplace (MCIIT, 2014). However, the majority of employers demonstrated little to no prior knowledge of these resources throughout our consultations.

In addition, immigrants do not necessarily settle where their skills are in demand. Of the 501,060 immigrants to Ontario between 2006 and 2011, an estimated 381,745 or 76.5 percent chose to settle in the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) (Gov. of Ontario, 2013).

Clearly, there is opportunity to realize improved labour market outcomes for immigrants by ensuring that they are better mapped to opportunities in the province. This could include, as multiple stakeholders suggested, directing greater resources towards marketing job and settlement opportunities in regions other than Toronto to new market entrants in Ontario.

The recommendations presented in this section of the report have been designed to improve the integration of international talent in the Ontario labour market through improved coordination of labour market integration and settlement services across all levels of government.

Recommendation 3.i: Renew the Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement (COIA)

The COIA was a landmark agreement that saw the Ontario government increase its immigration activities and the federal government significantly increase its spending on integration programs. The Government of Canada agreed to consult with Government of Ontario in the allocation of $920M in immigration funding over five-year period, beginning in 2005 (IRCC,2013). With the expiry of the COIA in 2011, Ontario is one of the few provinces without an immigration agreement with the federal government.

Despite the intent of the COIA, there were many challenges with the agreement in practice. For example, the federal government underspent by $225 million over six years (from 2005 to 2011) of the promised funding for settlement programs in the province. This decision compromised the ability of service providers to deliver integration services and programs. Furthermore, although the agreement included bilateral consultation mechanisms with the objective of coordinating provincial and federal integration programs, coordination between the federal and provincial governments remained suboptimal (Gov of Ontario, 2011).

The successful renegotiation of the COIA could reduce the duplication and administrative burden of immigration programs and services. Through improved coordination, the Governments of Canada and Ontario could be in a position to maximize settlement services investment to help newcomers integrate more quickly into the Ontario economy.

It is critical that the Governments of Canada and Ontario work together to renew the COIA to eliminate overlap of federal and provincial settlement services, maximize government investment, and close gaps in the provision of services throughout the province.

Recommendation 3.ii: Leverage the Municipal Immigration Information Online Program to develop a coordinated outreach strategy to retain immigrants in rural and northern communities.

Rural and Northern communities experience particular challenges with respect to attracting and retaining immigrants. One of the chief challenges identified by stakeholders throughout our consultations was the tendency for immigrants to feel isolated in these communities due to the absence of social support networks.

The Municipal Immigration Information Online Program was designed to address this challenge. Initially developed as part of the COIA in 2005, the program increased the online capacity, resources, and information provided to immigrants by municipalities, particularly at the pre-arrival stage (IRCC,2011). In the current framework, municipalities apply for funding under two project priorities: Municipal Immigration Information Online (MIIO) and Innovative Immigration Initiatives (Gov of Ontario.2013). The program has led to the launch of 28 municipal immigration portals representing over 120 communities in Ontario (IRCC, 2015e).

In its evaluation of the Canada Immigration Portal Initiative in 2010, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (now Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada) recognized that one of the greatest strengths of the Municipal Immigration Information Online Program “has been the development of federal/provincial/territorial/municipal partnerships in the creation and provision of a full spectrum of online, information, from the local to the national level” (IRCC, 2011). Few stakeholders, however, are familiar with government funded municipal immigration supports available online, including the municipal immigration portals.

Perhaps more concerning is that some online resources are outdated or no longer operational. One immigration portal, for instance, links to a ‘Newcomer Connections Calendar’ has not been updated since March 2015 (Brantford, 2016).

Given that these immigration portals likely constitute the introduction of many potential immigrants to Ontario municipalities, we recommend that the federal and provincial governments recommit to the Municipal Immigration Information Online Program through the renewed COIA. In order to leverage its investment in these portals, we recommend that the agreement include a provision to establish greater consistency among the design of the municipal immigration portals with the end user, namely potential immigrants, in mind. This could be achieved by adapting a structure consistent with the OntarioImmigration.ca site while maintaining municipal direction of content to reflect local priorities and circumstances. In particular, we recommend that all municipal immigration portals be made accessible in a multitude of languages comparable to those offered on the City of Toronto Immigration Portal. Furthermore, we recommend that the Government of Ontario work with the federal and municipal governments to better market these portals to potential immigrants.

The implementation of these recommendations will ensure that rural and Northern communities, in particular, are better positioned to market the advantages of settling in their communities to potential immigrants.

Recommendation 3.iii: Reopen immigration offices throughout the province to provide in-person services to refugees and immigrants.

In the 2012 Budget, the federal government announced that ‘Citizenship and Immigration Canada [would] change the way it operates in Canada and abroad by reducing overhead costs and continuing to streamline operations and program delivery to provide better value for Canadians’ (Flaherty, 2012). In order to achieve its savings target, CIC closed 19 immigration offices throughout the country (Cohen, 2012). In Ontario, this decision resulted in the closure of offices in Barrie, Kingston, Oshawa, Sault Ste. Marie, Sudbury and Thunder Bay.

The remaining ten immigration offices in Ontario are located in the following cities: Hamilton, Kitchener, London, Niagara Falls, Ottawa, Mississauga, Toronto, and Windsor (IRCC, 2016c) The concentration of immigration offices in the central and south-western regions of the province contribute to the challenge of cities in other regions, most notably the northwestern and northeastern regions of the province, to attract and retain immigrants in their communities.

Stakeholders emphasized the need for a federal strategy to attract immigrants to communities beyond Canada’s three major urban areas. The results of a 2016 survey conducted by the Ontario Chamber of Commerce support the claim that employers in communities beyond the Greater Toronto Area experience significant difficulties filling job openings. For instance, over 37 percent of Sudbury-based employers and 35 percent of Kingston-based employers surveyed responded that they had difficulty filling a job opening over the past 12 to 18 months because they couldn’t find someone with the right qualifications (OCC,2016)

Although IRCC offers itinerant services in these regions, stakeholders have commented that information pertaining to these services is very difficult to access. IRCC’s website, for instance, provides a list of areas served as well as the itinerant services to be provided. However, no information is provided as to the exact location of the temporary office or the materials that an applicant requires in order to be successful throughout the process. In addition, it is more difficult for immigrants in northern and remote regions of the province to access IRCC’s online resources – including the list of temporary offices – due to insufficient broadband connectivity in those regions.

In the interests of servicing immigrants, refugees and the communities in which they’ve chosen to settle, the federal government should re-open immigration offices throughout the province to provide reliable, face-to-face services to immigrants and refugees. We recommend that the federal government prioritize the re-opening of immigration offices in northern and remote communities where immigrants experience the greatest difficulty accessing IRCC’s resources.

CONCLUSION

Leveraging the skills and global connections of international talent in Ontario is critical to ensuring the province’s global competitiveness and future prosperity. The recommendations presented in this report reflect the priorities of employers and representatives of the immigrant community throughout the province.

Throughout the OCC’s consultations, stakeholders emphasized that relationships are key to the development of productive workplaces, positive immigrant labour market outcomes, and trade opportunities. Similarly, it is recognized that the successful implementation of the recommendations presented in this report will depend on the strength to the relationships between the federal government and other actors in the economy.

We recommend that the Government of Canada work with the Government of Ontario, chambers of commerce/boards of trade, immigrant partnerships and municipalities to market programs and services designed to facilitate the improved integration of immigrants into the labour market. Local chambers of commerce/boards of trade and immigrant partnerships, in particular, are well-positioned to help better map immigrants to opportunities, thanks to their networks within both the immigrant and business communities.

There is also an opportunity to leverage the province’s investment in postsecondary education. Ontario colleges and universities are the province’s human capital generators. Government and industry must coordinate to supply international students with the opportunity to pursue employment in Ontario post-graduation.

By strengthening its relationships with these actors and leveraging its investment in the suite of immigration and labour market integration programs available to Ontario employers and immigrants, there is an opportunity for the federal government to help reduce the costly skills gap and improve immigrant labour market outcomes in the province. We encourage the federal government to collaborate with all relevant stakeholders to foster greater prosperity in Ontario.

WORKS CITED

Advisory Panel on Canada’s International Education Strategy. 2012. International Education: A Key Driver of Canada’s Future Prosperity. Global Affairs Canada. Web. 28 Mar. 2016. http://www.international.gc.ca/education/assets/pdfs/ies_report_rapport_sei-eng.pdf.

Berthiaume, L. 2016. Liberals Plan for Huge Influx of Refugees, Immigrants Spouses at Expense of Skilled Foreign Workers. The National Post. http://news.nationalpost.com/news/world/liberalgovernment-is-planning-to-bring-in-a-record-of-more-than-305000-new-permanent-residentsin-2016.

CIC News. 2015. Canadian Employers: New Compliance Regulations and Penalties to Come into Force December 1. http://www.cicnews.com/2015/11/canadian-employers-compliance-regulationspenalties-force-december-1-116603.html.

Canada Visa. Canadian Experience Class Immigration Program. http://www.canadavisa.com/canadianexperience-class.html.

Canadian Chamber of Commerce. 2016. Immigration for a Competitive Canada: Why Highly Skilled International Talent Is at Risk. Ottawa.

City of Brantford. 2016. Newcomer Connections Calendar. https://mybrantford.ca/NewcomerConnectionsCalendar.aspx.

Cohen, Tobi. 2012. 19 Regional Immigration Offices Closing. O’Canada. Postmedia News. http://o.canada.com/news/19-regional-immigration-offices-closing.

Conference Board of Canada. 2013. The Need to Make Skills Work: The Cost of Ontario’s Skills Gap. http://www.conferenceboard.ca/e-library/abstract.aspx?did=5563.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection. 2016. Skilled Independent Visa (Subclass 189). Australian Government. http://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Visa-1/189- (Cited as Dept. of Immigration, 2016a)

Department of Immigration and Border Protection. 2016. Student Training and Research Visas Processing Times. Australian Government. https://www.border.gov.au/about/access-accountability/service-standards/student-training-and-research-visa-processing-times. (Cited as Dept. of Immigration, 2016b)

Flaherty, James, Hon. 2012. Jobs, Growth and Long-Term Prosperity: Economic Action Plan 2012. P. 263: House of Commons. Print.

Global Affairs Canada. 2013. Economic Impact of International Education in Canada – an Update. http://www.international.gc.ca/education/report-rapport/economic-impact-economique/index.aspx?lang=eng.

Government of Canada. 2016. Canada’s 2016 Immigration Levels Plan. http://news.gc.ca/web/articleen.do?nid=1038699.

Government of Ontario, 2011. Federal Actions Negatively Impacting Ontarians. Passport to Prosperity| 19

Government of Ontario. 2013. 2011 National Household Survey Highlights: Factsheet 1. http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/economy/demographics/census/nhshi11-1.html.

Government of Ontario. 2015. Immigration Programs 2015 Call for Proposals. http://www.grants.gov.on.ca/GrantsPortal/en/OntarioGrants/GrantOpportunities/PRDR014361.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2011. Evaluation of the Going to Canada Immigration Portal Initiative. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/portal/appendixC.asp. (IRCC, 2011).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2013. Immigration and Settlement in Ontario. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/laws-policy/agreements/ontario/can-ont-index.asp. (IRCC, 2013).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2014. Notice – Supplementary Information to the 2015 Immigration Levels Plan. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/notices/2014-11-06.asp. (IRCC, 2014).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2015. Determine Your Eligibility – Canadian Experience Class. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/immigrate/cec/apply-who.asp. (IRCC, 2015a).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2015. Express Entry: Background. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/employers/express-entry-system.asp. (IRCC, 2015b).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2015. Facts and figures 2013 – Immigration Overview: Permanent Residents. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/ resources/statistics/facts2013/permanent/12.asp. (IRCC, 2015c).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2015. Find out If You Need a Labour Market Impact Assessment. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/work/employers/apply-who.asp. (IRCC, 2015d).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2015. Living in Ontario. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. http://www.ontarioimmigration.ca/en/living/OI_HOW_LIVE_CITIES.html. (IRCC, 2015e).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2015. Provincial Nominees. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/immigrate/provincial/. (IRCC, 2015f).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2016. Check Application Processing Times. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/information/times/. (IRCC, 2016a).

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2016. Employer Liaison Network. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/hire/eln.asp. (IRCC, 2016b)

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. 2016. IRCC Offices in Canada – by Appointment Only. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/ information/offices/help.asp. (IRCC, 2016c).

Kustec, Stan. 2012. The Role of Migrant Labour Supply in the Canadian Labour Market. Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2012. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/research/2012-migrant/documents/pdf/migrant2012-eng.pdf.

Ontario Chamber of Commerce. 2013. Pre-Budget Survey. N = 2,059/Survey Date: January-February 2013.

Ontario Chamber of Commerce. 2016. Pre-Budget Survey. N = 853/Survey Date: December-January 2016.

Ontario Ministry of Citizenship, Immigration and International Trade. 2014. Ontario Bridge Training. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. http://www.citizenship.gov.on.ca/english/keyinitiatives/bridgetraining.shtml. (MCIIT, 2014).

Ontario Ministry of Citizenship, Immigration and International Trade. 2015. About Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program. http://www.ontarioimmigration.ca/en/pnp/OI_PNPABOUT.html. (MCIIT, 2015a).

Ontario Ministry of Citizenship, Immigration and International Trade. 2015. Ontario Human Capital Priorities Stream. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. http://www.ontarioimmigration.ca/en/pnp/OI_PNP_EE_CAPITAL_FAQ.html. (MCIIT, 2015b).

Ontario Ministry of Citizenship, Immigration and International Trade. 2015. Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program: Foreign Workers Stream. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. http://www.ontarioimmigration.ca/en/pnp/OI_PNPWORKERS_APPLY.html#display. (MCIIT, 2015c).

Roslyn, Kunin and Associates, Inc. 2012. Economic Impact of International Education in Canada – An Update. Government of Canada, Foreign Affairs and International Trade. http://www.international.gc.ca/education/assets/pdfs/economic_impact_en.pdf.

Simon, Bernard. 2014. Canada’s International Education Strategy: Time for a Fresh Curriculum. Canadian Council of Chief Executives. Business Council of Canada. http://thebusinesscouncil.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2014/06/Bernard-Simon-Canadas-International-Education-Strategy-FINAL.pdf.

Statistics Canada. 2015. Analysis of the Canadian Immigrant Labour Market, 2008 to 2011. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/71-606-x/2012006/part-partie1-eng.htm. (Statistics Canada, 2015a).

Statistics Canada. 2015. Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm. (Statistics Canada, 2015b).

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2016. Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/internationalstudent-flow-viz.aspx.

Zon, Noah. 2014. Immigration to Ontario Has Declined 33% Due to Federal Government Rule Changes. Mowat Centre. https://mowatcentre.ca/immigration-to-ontario-declined-due-to-federal-governmentrule-changes/.

ABOUT THE ONTARIO CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

For more than a century, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce (OCC) has been the independent, non-partisan voice of Ontario business. Our mission is to support economic growth in Ontario by defending business priorities at Queen’s Park on behalf of our network’s diverse 60,000 members.

From innovative SMEs to established multi-national corporations and industry associations, the OCC is committed to working with our members to improve business competitiveness across all sectors. We represent local chambers of commerce and boards of trade in over 135 communities across Ontario, steering public policy conversations provincially and within local communities. Through our focused programs and services, we enable companies to grow at home and in export markets.

The OCC provides exclusive support, networking opportunities, and access to innovative insight and analysis for our members. Through our export programs, we have approved over 1,300 applications, and companies have reported results of over $250 million in export sales.

The OCC is Ontario’s business advocate.

To learn more visit www.occ.ca or follow us @OntarioCofC

Passport to Prosperity: Ontario’s Priorities for Immigration Reform

Author: Kathryn Sullivan

ISBN PDF: 978-1-928052-29-6

©2016 Ontario Chamber of Commerce