Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Promise and the Missteps of Express Entry

- Express Entry: Notable advantages of the new system

- Major misstep: Requiring (in effect) a labour market test in Express Entry

- Misstep: Express Entry lacks a sectoral approach

- Misstep: Older senior executives are not valued

- Highly Skilled Talent and the Temporary-to-permanent Path

- Misstep: The occupations list is out of sync with reality

- Misstep: The compliance regime worsens the impact of discretionary decisions

- Misstep: Lack of fairness and transparency

- Misstep: Lack of an appeal process

- Misstep: Processing, resources and IT issues

- Education Sector Issues

- Delays in students’ applications

- Compliance chill for academic researchers and faculty

- Transition challenges in the post-secondary education sector

- Summary of Employers’ Issues Regarding Express Entry and the TFWP

- Conclusion

- Recommendations in this Report

- Appendix

Introduction: The Promise and the Missteps of Express Entry

“We must aggressively court skilled immigrants who, now more than ever, are being sought after by our competitor countries.”

– Liberal Party of Canada’s reply to the Canadian Chamber of Commerce in September 2015 during the election campaign

A total of 70% of major Canadian companies surveyed recently said that changes to the LMIA process have had a negative impact on their ability to recruit skilled workers through the economic immigration system.

– Survey findings, Canadian Employee Relocation Council, November 2015

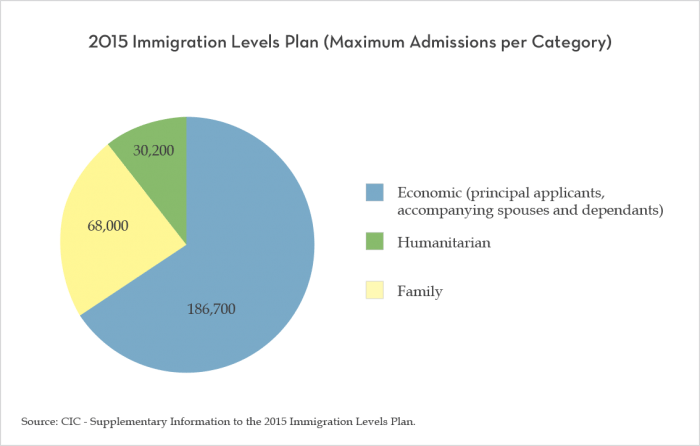

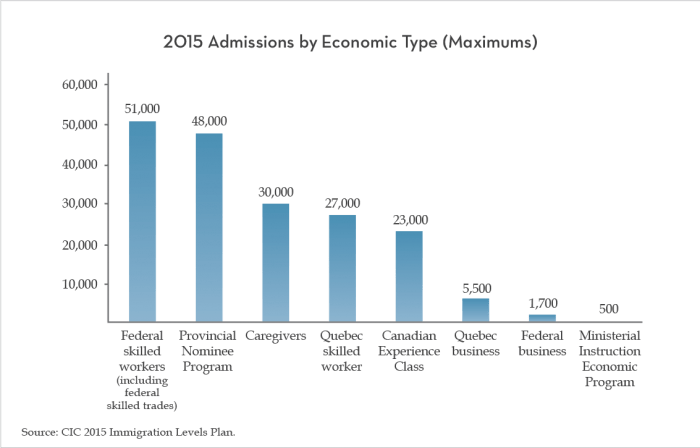

As the world’s most welcoming destination for newcomers (as a proportion of our population), Canada is truly an immigrant nation. Two-thirds of newcomers are invited through the economic streams of the immigration system. With forecasts of low GDP growth, persistently negligible productivity growth and a declining ratio of workers-to-retirees, Canada must take more interest in the economic potential of new immigrants.

Immigrants can help boost Canada’s innovation performance, which has lagged behind many

other developed countries.1 “Skilled and highly educated immigrants can also make important contributions to innovation in Canada,” according to the latest State of the Nation report of the Science, Technology and Innovation Council.2 “U.S.-based research has shown that immigrants are overrepresented as business owners, founders of high-tech start-ups, patent holders, Nobel Prize winners and exporters.”3

Recently, “Canada’s talent performance (in innovation) has showed mild signs of erosion against competitors,” according to the Science, Technology and Innovation Council.4

In the global competition for highly skilled talent, the government sought to improve the economic immigration system with the launch of the Express Entry application management system in January 2015. Yet, in an atmosphere of hyper-political reaction over temporary foreign workers, the government made policy choices that ultimately sacrificed the effectiveness of Express Entry. All the resources that were dedicated to the new system had a negative impact on the processing of temporary foreign workers. Express Entry became preoccupied with putting Canadians into jobs instead of bringing much needed highly skilled talent to Canada to contribute to job creation.

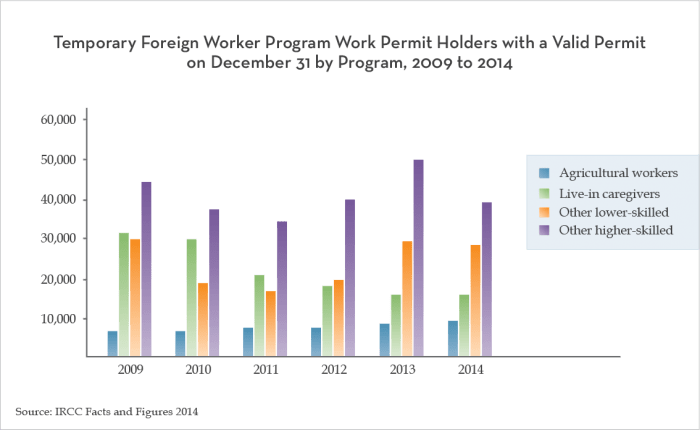

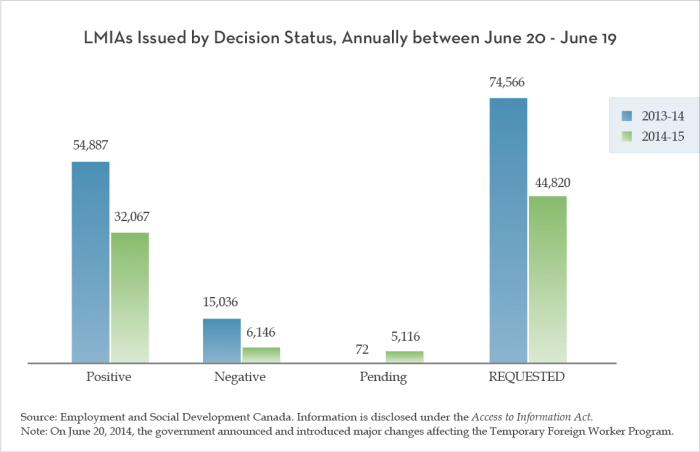

As a result, Canada appears to have invited far fewer highly skilled workers to work here on a temporary basis. There has been a 40% drop in higher-skilled work permit holders between 2013 and 2014 and a 45% drop in positive labour market impact assessments (LMIAs), which are required for work permits in the year, since June 2014.5,6

The original intent of Express Entry was lost, and, as captured in this report, the resulting problems, along with the solutions put forward by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, highlight the need to return to the system’s real purpose and opportunity.

One year after the launch of Express Entry, Canada risks losing its economic and competitive advantage when it comes to attracting highly skilled international talent. Fortunately, there are simple and efficient ways to mitigate and avoid that risk and undo the damaging impacts.

For the Canadian Chamber and its members who employ highly skilled international talent, the situation has become untenable and dismaying. The actual design of the system has had negative effects across high-value growth sectors, from high tech to financial services to academic research. Policy approaches that were born of suspicion, negativity and reprisal were applied to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and then similarly and inappropriately applied to Express Entry. For all the good work of government officials, the programs are falling short of their goals and creating inefficiencies within departments.

Chief among the missteps was the de facto requirement that a job offer be validated with a positive LMIA in order to achieve any certainty or predictability as to whether or when a foreign national will be permitted to apply for permanent residency.7 Not only is the LMIA a test of whether there are Canadians available to fill a position, but the compliance, enforcement and penalty regime for employers with LMIAs is daunting and overbearing.

The “Canada first” strategy for immigration has been subsumed by the “Canadians first” policy of the TFWP. The concept of attracting “the best and the brightest” is missing in action as the competitive model of Express Entry is currently undermined by the protectionist policy embodied in the LMIA tool.

This report explores the experiences of employers who are attempting to bring in highly skilled international talent. It reveals that the employer’s role in selecting the most qualified and skilled talent, and thereby sending signals on labour market demand, has been thwarted. Immigrants’ economic outcomes will suffer if they do not arrive with job offers. The impacts of the roadblocks and delays that have resulted from the changes within the past two years are accompanied by suggestions for improvements in the short-term.

“Express Entry is the most progressive system anywhere in the world, but it is only fantastic if it meets its goal,” says Rohail Khan, President of Skills International, a company that is working with employers and communities to attract international talent.

The new government can simply and effectively adjust the system to reinstate the demand-driven competitive focus that employers bring to immigrant selection.

Express Entry: Notable advantages of the new system

The Express Entry system is a most promising reform of selecting and processing applicants for economic immigration. The original objectives of the system, such as giving employers, provinces and territories a role in immigrant selection and speeding up the processing times of applications, are ones the Canadian Chamber and its members embrace. These are among the positive features of Express Entry:

- Processing of permanent resident applications (those that are fully completed following an invitation to apply) is much faster.

- 80% of complete applications (by candidates who received an invitation to apply) will be processed within six months.

- Applications are now fully electronic.

- Candidate selection is intended to be demand-driven based on scores on human capital factors as well as either a job offer or a provincial nomination.

- No list of in-demand occupations and no caps on the numbers of applicants by occupation.

- No charge for an applicant to enter a profile in the system.

Now is the time for a sober, thoughtful review of what Canada can accomplish through economic immigration. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) role in “fostering Canada’s economic development” and improving the immigration system to “benefit Canada by targeting skills Canadian employers need” is laudable.8 The Canadian Chamber and its members welcome the opportunity to work with the government to ensure immigration enables Canada’s prosperity and immigrants’ success.

Major misstep: Requiring (in effect) a labour market test in Express Entry

Giving employers a role in the selection of immigrants is generally considered the best way to ensure an immigration system is “demand-driven.” The Express Entry system was intended to address the relatively poor labour market outcomes of immigrants to Canada by addressing what researchers have agreed is one of the key causes: a lack of arranged employment on arrival.9

For close to two years prior to the launch of Express Entry in January 2015, the government consulted with employers, businesses and industry associations, among others, and developed a system predicated on those ideas. Then, after overhauling the TFWP, the government undermined the whole “convergence of supply and demand” through Express Entry by introducing an LMIA requirement to validate employers’ job offers.

It was a misstep that has reverberated throughout every constituency that relies on the immigration system to bring in sought-after talent to Canada. From highly skilled video game developers to top-flight researchers and skilled trades workers, a wide range of talent is finding it extremely challenging to come Canada for work and to apply for permanent residency.

Unfortunately, for temporary high-skilled workers seeking to transition to remain in Canada, Express Entry does not alleviate the many obstacles in their path. “Applying for permanent residence entails challenges such as navigating existing immigration programs and intransigent decisions by some immigration officers,” say the authors of a new IRPP report, Temporary or Transitional?, which offers new insights into the lived experience and human toll of coping with a frustrating, risky and opaque system.10

Recommendations

The Express Entry system should provide points:

- For a job offer, without requiring an LMIA to validate it.

- Instead, IRCC should create a test for employers to demonstrate they are a legitimate employer, using criteria similar to those in the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program, for example. The test could also build on the Arranged Employment Opinion approach that was previously used in the Federal Skilled Worker Program until May 2013.

- Alternatively, IRCC should consider a permanent employment contract as a valid job offer for an employee who has been working for the employer for one or more years.

- To a foreign national who is in Canada in an LMIA-exempt category within the International Mobility Program (IMP).

Canadian Chamber members report that the LMIA process to support temporary workers’ entry is almost unusable for most employers, especially small businesses. Worse, it is now a requirement for job offers for permanent residency applicants who wish to compete successfully to come to Canada.

“The LMIA requirement is a tool that is ill-suited to the selection of permanent residents because its logic is based on the protection of certain temporary jobs,” says Carl Dholandas, Counsel at Baker and McKenzie LLP. “It is not designed to measure long-term labour market demand. Express Entry and the Federal Skilled Worker Program are recruitment tools to add the best people for years to come,” he adds.

It is always easier and less expensive for companies to recruit and hire locally than internationally. They recruit from abroad when they cannot find qualified workers in Canada. Industry and skills shortages drive employers in some sectors to look abroad.

Two competing policy principles are at play, according to Ilia Burtman, a former director of the immigration selection branch of the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration and now, Managing Director of InsightEdge Inc. On the one hand, IRCC wants to facilitate employers’ access to a pool of international talent and on the other hand, it does not want employers to look at international candidates because the government wants Canadians first in the jobs, he says.

The two processes—the LMIA and the Express Entry system—are also intended to serve two different functions, say other commentators. The LMIA function is to protect Canadian workers, whereas the Express Entry system is to maximize the labour market outcomes of immigrants. Neither facilitates the attraction of the “best and the brightest.” While the Express Entry is a competitive model, by incorporating the LMIA, it adds a minimum threshold philosophy, not an excellence philosophy, to the model.

“Economic needs should become an even larger factor in the selection of immigrants.”

– Don Drummond, Evan Capeluck and Matthew Calver, The Key Challenge for Canadian Public Policy: Generating Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth, Centre of the Study of Living Standards, September 2015

“The federal government’s Temporary Foreign Worker program and accompanying so-called ‘Express Entry’ system is mired in red-tape impediments. Long-time employers of immigrants seeking permanent Canadian residency must post those jobs. That’s something employers are loath to do, as it signals upheaval in the ranks of their key personnel. These programs need to be revised to expedite permanent residency applications for immigrants who have worked in Canada for more than a year.”

– David Olive, “Why immigration is a chequebook issue.” Toronto Star. Oct. 16, 2015

With the threat of punitive fines imposed at the discretion of public servants and with no quasijudicial appeal process available to employers, the LMIA enforcement and penalty regime has created a chill among employers. “Based on my experience, I don’t think any company today is going to allow someone to submit an LMIA and open itself up to the rigidity and severity of compliance reviews, especially when the rules for compliance have not been clearly defined,” says an HR executive with global recruiting responsibility. His company’s legal department no longer supports using LMIAs for hiring international employees.

The irony of the LMIA requirement is that, while Express Entry is intended to increase the percentage of newcomers who are employed, the system does not recognize newcomers who are already employed in Canada and who are already contributing to the economy, but doing so without an LMIA.

“We would be losing valuable talent if we got rid of these employees when they have already been contributing to Canada for several years,” says Dholandas. “At that advanced stage, they have already integrated well and have a strong case for permanent residency.”

For employees who cannot get permit renewals in time, their Canadian employers may end up sending them home or relocating them to the U.S. or to other countries to do their jobs.

Employers suggest that if the government needs a test of genuineness of the job offer, the fact that an individual has been working for a while in a highly skilled job at above the prevailing wage should be rewarded. An LMIA is not an appropriate test for the validity of a job offer or of the legitimacy of an employer; an LMIA is a labour market test.

IRCC officials believe candidates will be selected on the basis of human capital alone and without a job offer backed by an LMIA. However, if a proportionately high number of candidates are admitted to Canada without job offers in hand, as has occurred prior to Express Entry, then the prospect for improved labour market integration of immigrants is reduced.

Express Entry: Notable advantages of the new system

Express Entry’s policy objectives are to address Canada’s economic needs and the relatively poor income and employment outcomes of immigrants compared to Canadian-born workers.

“We don’t necessarily need a sea-change in policy objectives, which are to increase economic immigration and to make sure we are bringing people with better language skills in one of our official languages and with educational credentials that can be recognized,” says Carl Dholandas.

Employers in certain high-value sectors, such as information technology and the video game sector, however, are experiencing a conflict between federal immigration policies and provincial economic development objectives.

One example is the investments in the video gaming industry in provinces such as Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. There is an understanding that the industry will require talent from outside of Canada in order to develop and grow, but then the federal government creates roadblocks through its immigration policies.

Recommendations

The government should:

- Dedicate a number of Service Canada officers for specialized knowledge of certain industries that are high-value and high users of the programs within Express Entry.

- Explore reintroducing a dedicated track for the assessment of applicants in the digital technology sector, along the lines of the Tech Nation Visa Scheme in the U.K.11

Ubisoft’s circumstance exemplifies the conflict that can arise, threatening to undermine the economic benefits for Canada flowing from international talent. The multinational company has two jobcreation objectives—totalling 800 positions in Ontario and 600 additional positions in Quebec. Both objectives are tied to provincial contracts and programs. Provincial governments have made strategic decisions to improve their economy and design programs to stimulate investment by companies and industries that are expected to generate positive economic impacts. The colleges and universities and the ecosystem surrounding these industries plan and make decisions based on these objectives and on the strategic choices made by the provincial governments.

All of these efforts and the economic growth that comes with them are undermined when the highly skilled workers—who are attracting projects, generating innovation and training local talent—cannot work in Canada or cannot come to Canada because the system is too slow, too incoherent or just not focused on strategic economic objectives.

Misstep: Older senior executives are not valued

Recommendations

The Express Entry system should provide extra points to senior experienced individuals in positions at the executive level in NOC O.

Youth is rewarded significantly in the Express Entry system. Candidates between the ages of 20 and 29 received the maximum 100 points for age, whereas anyone aged 45 and over received no points at all. Given the way the points are allocated in Express Entry, there is a tendency to undervalue, to a much greater extent, the older mid-career executive with substantial senior work experience. “If their experience is foreign and they are over the age of 40 or 45, they have a much slimmer chance of qualifying under Express Entry’s current scoring system,” says Dholandas.

In fact, employers note that relatively new graduates with degrees in Canada may score well, but people with degrees and five to 10 years of work experience are scoring very low without an LMIA—and many employers refuse to submit an LMIA.

Highly Skilled Talent and the Temporary-to-permanent Path

“Two-step immigration”—the process whereby international talent arrives in Canada to work on a temporary basis and then applies for permanent residency—is declining. In the first quarter of 2015, there was a 37% drop in the numbers of visas issued to TFWs compared to the first quarter of 2014. Although the data by category are not yet available, it would be wrong to assume the entire decrease was among low-skilled workers. Highskilled workers have comprised at least half of the TFWs in recent years across the four categories of high-skilled, low-skilled, live-in caregivers and seasonal agricultural workers.

There has been a 45% drop in the number of positive LMIAs issued in the year following June 20, 2014, when the major changes to the TFWP were announced.

These data give rise to questions such as: Are the LMIAs being inappropriately denied without valid reason? Are employers not attempting to get LMIAs because of the threat of a punitive compliance and enforcement regime?

Based on members’ experiences, this impact has hit highly skilled talent. Yet historically, the TFWP has always been focused on highly skilled talent; it was only opened up to lower-skilled workers in 2002 (although the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program has existed in some form since the 1960s).

Before the new rules in 2014, talent with an economic multiplier impact could come to Canada with far fewer obstacles than they and their would-be employers now face. One employer mentions the kind of talent who has created brands for a company—with one brand now employing 150 people based on the idea of one foreign national.

“Robust immigration and multiculturalism policies were also cited as strong assets that have led multinational enterprises (MNEs) to enhance their presence in Canada. The ability to bring talent to new jurisdictions quickly and efficiently is essential for large companies with global operations. Moreover, a country’s openness to other cultures is a crucial factor for MNEs that routinely move talent across international borders.”

– Excerpt from the report Winning Global Mandates: Lessons from Canadian Leaders, Public Policy Forum, May 2015

Think of the even greater impacts that a single skilled goalie in a professional hockey league can have. When the goalie’s team heads to the playoffs, the team’s success has positive economic spin-offs in terms of employment and spending in the team’s community. And it stems partly from the entry of one talented individual into Canada, like former Canuck player Eddie Läck from Sweden.

Call it the trickle-down effect of highly skilled talent. The positions may be few in number at a firm like Google Canada, but they can have an important impact on the opportunities and amount of work here in Canada, says Colin McKay, Head of Public Policy and Government Relations at Google Canada.

Senior people train local talent who can then increase the impact of the industry in the economy, says one employer. “It is good for local talent to have these senior people from other countries. These foreign nationals create the senior people of tomorrow,” says Nathalie Verge, Director, Corporate Affairs at Ubisoft.

Government should focus on the skills sets with global impact and allow firms to become stronger by working on international projects and breaking out of the Canadian branch plant mentality, says Google’s McKay. “It’s about people working on international teams, trying to get into the country and to work,” he adds.

The recent lament of a Canadian start-up entrepreneur reflects what is at stake through our immigration policy. When he found the best candidate for a position was an American, he was disappointed that her LMIA application was turned down, and she could not work in Canada. As an alternative to bringing her into Canada, he hired her and let her set up shop and hire staff in the U.S.12 By refusing a foreign national to grow a Canadian firm, the firm ended up adding jobs in the U.S. rather than at home.

With all the changes since June 2014, employers are highlighting the inconsistencies and the lack of certainty in processing and decisionmaking, which is ultimately having an impact on companies’ plans for growth. Employers face applications being rejected for relatively minor errors in how they were completed. In fact, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) issued an internal bulletin to TFWP officers on June 20, 2014 on “How to Handle Incomplete Applications,” which states that “Applications for Priority Processing with any incomplete elements, even if it is a quick call (to the employer), should be placed in regular processing.”13

One immigration lawyer believes that fear has gripped ESDC and Service Canada officers who are “compelled to follow policy direction as if it was legislation.”

This results in inefficiency, a waste of the department’s resources and a duplication of effort. It is a costly and opaque process for the employer, for the foreign national seeking to work in Canada and for government employees who will look at the same file another time when the employer re-applies. It would be more effective and respectful of the time and effort put into the first application if such errors could be addressed directly and expeditiously with the employer or applicant.

“With all the bureaucracy and the internal guidelines, we don’t know enough and, often, we do not find out (about rules or errors) until after we are processing TFW or PR (permanent residency) requests,” said one employer. “This is really having an impact. But it can be fixed without much of a burden for government.”

IRCC and ESDC could change the way they communicate the rules and ensure they are applied as consistently as possible across the country.

Recommendations

The government should:

- Encourage IRCC and Service Canada officers to improve the level of service; for example, Service Canada officers should be urged to call employers to make modest corrections or additions to complete their applications.

- Allow employers seeking highly skilled talent to shield salary information from their job postings, or post broad salary ranges, to achieve non-disclosure of competitive salary information.

Members report it is almost impossible to speak with visa officers at IRCC; there is virtually no contact at all. This matters particularly when a project in Canada depends on the arrival of international talent, and the employer has time-sensitive commitments to meet.

In addition, ESDC should allow Service Canada officers to be flexible and use judgment, even as they apply the rules consistently.

“At least if we know what we need to do to get one person in Canada in a few months, we can proceed accordingly,” said one employer. “If the criteria are more restrictive, at least we will know what they really are and that they are going to be applied consistently.”

Misstep: The occupations list is out of sync with reality

Employers of high-skilled talent are finding themselves challenged through the LMIA and the IMP process. For many positions, it starts with the National Occupation Classification (NOC) codes and the fact that Service Canada officers may not be identifying the roles correctly or the codes may be too outdated for an appropriate match. The match matters because the choice of NOC code or occupation then determines the prevailing wage that the officer will use to assess the LMIA request.

Recommendations

The government should:

- Remove the NOC code requirement wherever feasible in order to recognize the changing nature of occupations and to avoid confusion and unnecessary and costly errors by government officials.

- Update the listed occupations (NOC codes) to actually match the industry occupations.

- Improve the labour market information to reflect industry reality.

“It’s like a seek-and-search mission,” says Rohail Khan, President of Skills International. “Employers cannot figure out a NOC code that an employee fits in, and that is the cause of a lot of mistakes.”

“LMIAs cannot handle the analysis of the skills set in the marketplace,” says one employer. “You are asking people to assess LMIAs for traditional roles when the actual role is often very different.”

“Why do we even have the NOC codes?” asks an employer, who suggests looking at the way Australia and the U.K. are operating using a minimum salary level approach. “How simple would that be to get rid of the complexity?”

Misstep: The compliance regime worsens the impact of discretionary decisions

A massive over-reaction by the government in 2014 regarding the integrity of the TFWP and the need to punish bad actors resulted in a punitive set of policy and operational changes that have essentially thrown the other 95% of employers into a tailspin, says an immigration lawyer.

As of December 1, 2015, a highly restrictive compliance, enforcement and penalty regime came into force, affecting all employers of temporary foreign workers, including those who did not require an LMIA and those with LMIAs. There are fines of up to $100,000 per worker per violation, with a maximum of $1 million in fines per employer per year, as well as the potential for permanent bans from the program and public naming and shaming by being listed on the government’s website of violators.

The penalties would not be an issue if there was a clear, transparent and fair system in place. Unfortunately, employers and lawyers report that the system is so unpredictable that many employers are likely to be punished inappropriately or inadvertently. Trust goes both ways: the government officials need to trust the employers who use the system, and the employers, equally, must be able to trust the system they are relying on.

Recommendation

To be transparent, the government should release the results of its compliance audits and enforcement on an annual basis and evaluate whether the rate of non-compliance warrants the high ratio of inspections.

One in four employers will be inspected each year as a result of the government allocating additional resources for Service Canada and CBSA. The cost of the compliance and enforcement regime is paid for by employers through fees for LMIAs and compliance fees.

“Why create increased regulatory burden across the board and increased anxiety for everybody if most employers are law-abiding?” asks Burtman. “Because of that approach, the government is also unintentionally generating outcomes that are counterproductive to what it wants.”

Additionally, with LMIA-exempt work permits, there is no proper channel for employers to communicate to IRCC any minor condition changes, such as a title change in the same NOC code or a salary increase. This creates a discomforting risk for employers when one of the conditions placed on all employers of TFWs in Canada is to:

- Provide the foreign national with employment in the same occupation and substantially the same, but not less favourable, wages and working conditions as outlined in the foreign national’s offer of employment.14

Misstep: Lack of fairness and transparency

Recommendation

The government should develop a fully transparent set of guidelines and criteria regarding the LMIA and the TFWP so that everyone is following the same playbook.

The principles of fairness, objectivity and transparency should be central to the government’s administration of programs governed by legislative statute.

When the enhanced compliance regime for the TFWP and LMIAs was proposed in the fall of 2014, the Canadian Chamber urged the government to balance the discretion of civil servants, who can impose severe fines and program bans, with procedural fairness, starting with transparency. Both elements are still lacking from the current regime.

Discretionary decisions made by administrative decision-makers should be relevant, reasonable and consistent, with the process free of any abuse. Unfortunately, this has not been the case with past LMIAs. It is imperative to the overall success and economic well-being of Canadian businesses that the administrative decision-makers of the LMIAs and the TFWP be subject to the standards outlined under Canadian administrative law.

Given the inconsistent and contradictory information that employers receive from Service Canada officers handling these applications, including those in the same office and those in different provincial offices, the Canadian Chamber is concerned that employers trying to follow the rules will nevertheless be subject to incorrect decisions or, during compliance audits, subject to unwarranted and harmful fines and bans.

Under the newly enhanced compliance framework, further powers are vested in public servants, who will use it in a discretionary manner, and that power will lead to pecuniary sanctions that are easy to impose and difficult to challenge—notwithstanding the training of the inspectors.

Misstep: Lack of an appeal process

Recommendations

The government should adhere to the principles of fairness and due process under administrative law and take the following steps with regard to the compliance regime for the TFWP:

- Place all of the enforcement power into the hands of an administrative body, such as a quasi-judicial body or tribunal.

- Establish an appeal process for the compliance regime under a quasi-judicial body or tribunal; the Social Security Tribunal is one such option to consider, in light of its multi-faceted role.

Considering the severe and disproportionately punitive nature of the penalties that employers are subject to, there should be judicial oversight. The power to issue administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) usually resides with a tribunal. If a quasijudicial body is not in place, there may be due process concerns. Decision-making on major fines and potential bans from the program should not be decided by public servants outside a judicial body, as it is now.

Another serious criticism of the new compliance regime is that it lacks an appeal process as one would expect with discretionary decision-making under administrative law. While the regulations issued in July 2015 give employers 30 days to respond in writing before a final determination is issued regarding non-compliance, there is no appeal process.

Misstep: Processing, resources and IT issues

With the government’s promise to process Express Entry applications for permanent residency within six months, there seems to have been a shift in resources away from other processing priorities, such as the Case Processing Centre in Vegreville, Alberta which processes work permit, study permit and visitor extensions. Based on members’ experience, there are now serious and impactful delays in processing temporary work permit renewals through Vegreville, with current processing times reported by IRCC at 110 days or higher.

Recommendations

The government should improve processing times and act on its commitment to create new performance standards for services, including streamlining applications, reducing wait times and providing money-back guarantees.

IRCC and ESDC should create forums for ongoing dialogue (via webcast, for example) with representatives of key stakeholders of Express Entry, the TFWP and the IMP in order to communicate information and concerns amongst interested parties and with government officials.

There are human impacts resulting from these delays: immediately after the expiry of a work permit, a foreign national loses his or her provincial health coverage. To mitigate these risks, some employers are preparing work permit renewals almost five months in advance.

Additionally, the computer system is manifesting errors and inconsistencies that may be the result of glitches early in its deployment. According to immigration lawyers, two people that file almost identical applications can have two different experiences at almost every stage. There is a lack of predictability, resulting in a lot of frustration. As one lawyer noted, “The IT system is not what it should be, and IRCC needs that feedback.”

The system is resulting in a lot of rejections and refusals that seem either inadvertent or certainly unnecessary. “If you don’t do it exactly the way they want, the application will be rejected,” says one employer who had an application rejected because the word “permanent” was not in the job offer.

For the best chance at accuracy, many law firms with immigration practices advise clients to sit with lawyers and allow them to complete the application on their behalf.

Education Sector Issues

Delays in students’ applications

International education is a microcosm of the global competition for talent. It is a competition that is fought on the basis of a country’s educational reputation, the opportunity to immigrate and the timeliness of entry. In 2014, Canada was ranked as the seventh most popular destination for foreign students.15

According to 2013 data, of the 293,505 international students studying in Canada, 55% were attending universities, 26% were at another post-secondary institution or at a trade school and 16% were at secondary schools.16

The federal government’s International Education Strategy has a goal of doubling the number of fulltime international students to more than 450,000 by 2022.17 Approximately 50% of international post-secondary students in Canada are interested in exploring permanent residency.18

Yet, academic administrators believe that in the past couple of years, either government resources have been shifted away from processing some types of visa permits or new funding may have been devoted to the Express Entry system, leaving visa processing without sufficient funding or resources to support the growth in demand.

“Students want to know how quickly they will get their visas,” says Andrew Ness, Director, International Service at Sheridan College. “The American system can turn a visa around in 10 days, and Canada takes months, sometimes as long as four months. Co-op work permits (which are separate from study permits and are required for all international students in co-op programs) are taking over 100 days, which is ludicrous.”

Recommendations

- Reduce the processing time for study permits and visas to compete with other international markets such as the U.S. and Australia.

- Allow a study permit to incorporate a co-op work permit, rather than require international students to apply for each permit separately.

- Act on its commitment to credit the time spent in Canada for post-secondary education toward international students’ residency time for citizenship purposes.

Additionally, post-secondary education administrators are discouraged from playing a critical role in leveraging international students’ interest in staying in Canada and potentially immigrating. To allow them to play that role, a new credentialing regime for immigrant consultants on campus is being introduced.

In the meantime, post-secondary education employees are all required to attain certification from the Immigration Consultants of Canada Regulatory Council (ICCRC) before advising or assisting international students on immigration matters. “Students come in every day to ask for advice for their Post-graduate Work Permits, but staff members cannot help them if they are not certified,” says Ness, who would favour an easier step for his staff to be regulated than the new system.

“If Canada wants an aggressive pursuit of really skilled young people, how do we maintain the trajectory toward the goal?” asks Ness.

Compliance chill for academic researchers and faculty

In another unfortunate twist, employers of foreign nationals in Canada on a temporary LMIA-exempt basis under the IMP have become subject to a compliance and penalty regime that was developed for employer-employee contractual relationships that do not always exist for permitholders under IMP categories.

- When an inspection finds that an employer is non-compliant, the employer could face an administrative monetary penalty, a ban from hiring foreign workers and, in serious cases, a criminal investigation and prosecution. The adoption of this system will mean that all employers, whether they are hiring LMIA-exempt foreign nationals or temporary foreign workers through the LMIA process that has determined that there are no Canadians available for the job, will face the same level of scrutiny in their hiring and treatment of foreign workers.

- Source: CIC. Notice – Changes to strengthen employer accountability under the International Mobility Program. Feb. 9, 2015.

The new compliance regime and the employer portal for the IMP create a more formal legal obligation between employers and employees. However, not all foreign researchers are viewed as employees by the universities. Universities are losing visiting researchers because some legal departments are not allowing the universities to go forward with offers, says Gail Bowkett, Director, Research, Policy and International Relations at Universities Canada.

“On the one hand, the federal government is supportive of universities’ role in bringing highly skilled talent to Canada and the necessity of being engaged in international research collaboration,” says Bowkett. “On the other hand, the new employer compliance regime and the employer-employee relationship required by the IMP create challenges in bringing in visiting professors, researchers and students who do not necessarily fall into the category of employees.”

Transition challenges for faculty, researchers, and students at post-secondary institutions

Foreign nationals who have been hired to fill Canada Research Chairs at universities typically come to Canada under an exemption code through the IMP. Tenure-track faculty positions may be filled via the TFWP. In either instance, challenges arise if the individuals seek to transition to permanent residency status. Canada Research Chairs are typically older and will not score any points for age (i.e. youth) in the Comprehensive Ranking System. For tenure-track faculty, the challenge is that IRCC requires job offers to be for permanent positions. Since tenure-track appointments often have an “end date,” which specifies the duration of time that a faculty member can remain untenured, IRCC does not view these job offers as permanent. However, this stipulation is part of the normal probationary process for new tenure-track faculty and does not signify that the offer is being made on a temporary basis only.

There are several other concerns, as outlined by the University of Calgary:

- Lack of communication and consistency in the interpretation of regulatory changes and/or IRCC practices.

- Lack of ability for LMIA-exempt academic employees (such as CRC and CERC Chairs and NAFTA Professionals) to successfully apply for permanent residency under the Express Entry system as they are not awarded points for having a permanent job offer.

- Express Entry denials for tenure-track faculty. Although LMIA-based, these appointments are viewed as “non-permanent” by IRCC officers.

- Lack of ability for employers to communicate with IRCC on issues related to their foreign employees.

- Extremely long processing times of inland work permit extension applications.

The University of Calgary has lost some very good candidates due to delays or inabilities to navigate the system. “A number of our institutions, especially research-based universities, have lost world-class senior administrative candidates—in positions such deans—because of the delays in immigration timing and the uncertainty in results,” says Elizabeth Cannon, President of the University of Calgary. At one institution, there are currently several tenure-track and contingent term (medicine) appointees whose permanent residency applications are currently in progress through the Express Entry system, but they fear they may eventually be refused by IRCC as their appointments may be interpreted as “non-permanent.”

Prior to Express Entry, most students applied for immigration through Canadian Experience Class (CEC). When they met the requirements in CEC, they were more likely to be successful than not, according to several post-secondary education administrators. There was some certainty and confidence among the students then about their candidacy for immigration.

Now the invitations to apply for permanent residency are based on where candidates sit in a comprehensive ranking system based on points. Students face uncertainty and competition from people who have never spent any time working or studying in Canada but who could attain more points due to a job offer.

Recommendation

IRCC should consider awarding comprehensive ranking system points to international students who have completed full-time post-secondary studies in Canada.

Another drawback to Express Entry is the lack of transparency. When invitations to apply are issued, IRCC does not publish how many were issued for CEC or for particular sector. In addition, IRCC displays only the lowest score for each draw, not the numbers at points in the range.

“It is still quite challenging for students to get an LMIA or a PNP (Provincial Nominee Program),” says John Porter, Director, International Admissions and Student Services at George Brown College. As LMIAs are meant to test the Canadian labour market to ensure there are not similarly qualified Canadians available for the role, Service Canada officials will only infrequently approve an LMIA application for a position to be filled by a recent university graduate.

Summary of Employers’ Issues Regarding Express Entry and the TFWP

- LMIA process is unusable for many employers and is very challenging for others.

- Transition plan requirement and tracking is onerous under the LMIA.

- Threat of compliance audits and penalties scares off many potential LMIA applicants.

- Advertising requirements for LMIAs for permanent residencies are inappropriate.

- Point scores create issues, especially for older experienced workers.

- Uncertainty for those in the Express Entry pool with a job offer that is not supported by an LMIA.

- Permit renewals/expiration and timing issues.

- Specific situations vis-à-vis the officers only speaking at a high level or hypothetically.

- Technology and process issues; e.g., inadvertent or minor errors, which could cause the rejection of an application.

- Processing issues and timelines varying by location of visa office or Service Canada office.

- Concerns about the discretion of CBSA officers at border points of entry.

Conclusion

Immigration for Canada’s economic competitiveness

Canada’s ability to recruit and integrate international talent into its labour force will increasingly affect its chances to fully realize its economic prosperity. Express Entry was designed and intended to contribute to that goal, but the government thwarted its own efforts with policy decisions taken in a politically overheated atmosphere.

The government can now take a step back and reclaim the opportunity for a truly competitive and effective immigrant selection model. It can adjust instructions and regulations underpinning Express Entry and also address key issues affecting high-skilled talent in the TFWP and the IMP as candidates for Express Entry.

“The evidence is clear that well-managed immigration can contribute to economic growth, generate jobs, promote innovation, increase competitiveness and help address the effects of aging and declining populations,” according to a report of the World Economic Forum.19

Workforce planning is becoming more strategic and demanding for employers. Part of their response to fill skills gaps should be to tap into every source of talent, including internationally trained individuals who are either here in Canada or are eligible to immigrate here.

Immigration matters too much to Canada’s labour market for business not to be engaged in the system. With employers’ involvement, Canada can better align immigrant talent with labour market needs and future economic prosperity. Through gainful employment that fully capitalizes on their skills, immigrants will also enjoy both economic and social prosperity here.

It will be a win-win-win for immigrants, business and Canada.

Recommendations in this Report

The government should:

- Provide points in Express Entry for a job offer, without requiring an LMIA to validate it. Instead, IRCC should create a test for employers to demonstrate they are a legitimate employer, using criteria similar to those in the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program, for example. The test could also build on the Arranged Employment Opinion approach that was previously used in the Federal Skilled Worker Program until May 2013.

- Provide points in Express Entry to a foreign national who is in Canada in an LMIA-exempt category within the International Mobility Program.

- Dedicate a number of Service Canada officers for specialized knowledge of certain industries that are high-value and high users of the programs within Express Entry.

- Explore reintroducing a dedicated track for the assessment of applicants in the digital technology sector, along the lines of the Tech Nation Visa Scheme in the U.K.

- Provide extra points in the Express Entry system to senior experienced individuals in positions at the executive level.

- Encourage IRCC and Service Canada officers to improve the level of service; for example, Service Canada officers should be urged to call employers to make modest corrections or additions to complete their applications.

- Allow employers seeking highly skilled talent to shield salary information from their job postings, or post broad salary ranges, to achieve non-disclosure of competitive salary information.

- Remove the National Occupation Classification (NOC) code requirement wherever feasible in order to recognize the changing nature of occupations and to avoid confusion and unnecessary and costly errors by government officials.

- Update the listed occupations (NOC codes) to actually match the industry occupations.

- Improve the labour market information to reflect industry reality.

- Release the results of its compliance audits and enforcement on an annual basis and evaluate whether the rate of non-compliance warrants the high ratio of inspections.

- Develop a fully transparent set of guidelines and criteria regarding the LMIA and the TFWP so that everyone is following the same playbook.

- Place all of the enforcement power into the hands of an administrative body, such as a quasi-judicial body or tribunal.

- Establish an appeal process for the compliance regime under a quasi-judicial body or tribunal; the Social Security Tribunal is one such option to consider, in light of its multi-faceted role.

- Improve processing times and act on its commitment to create new performance standards for services, including streamlining applications, reducing wait times, and providing money-back guarantees.

- Create forums at IRCC and ESDC for ongoing dialogue (via webcast, for example) with representatives of key stakeholders of Express Entry, the TFWP and the IMP, in order to communicate information and concerns amongst interested parties and with government officials.

- Reduce the processing time for study permits and visas to compete with other international markets such as the U.S. and Australia.

- Allow a study permit to incorporate a co-op work permit, rather than require international students to apply for each permit separately.

- Act on its commitment to credit the time spent in Canada for post-secondary education toward international students’ residency time for citizenship purposes.

- Consider awarding comprehensive ranking system points to international students who have completed full-time post-secondary studies in Canada.

Appendix

Canada – Temporary Foreign Worker Program Work Permit Holders by Program and Year in which Permit(s) Became Effective, Q1 2010 to Q1 201520

| Programs | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Total unique persons | Q1 | Total unique persons | Q1 | Total unique persons | Q1 | Total unique persons | Q1 | Total unique persons | Q1 | Total unique persons | |

| Live-in caregivers | 5,281 | 17,117 | 4,261 | 16,670 | 4,129 | 12,672 | 3,088 | 11,079 | 3,243 | 11,964 | 2,513 | 2,513 |

| Agricultural workers | 8,327 | 31,731 | 8,737 | 33,657 | 9,330 | 35,098 | 9,352 | 37,595 | 9,895 | 39,550 | 10,184 | 10,184 |

| Other Temporary Foreign Worker Program work permit holders | 15,684 | 56,896 | 14,504 | 61,687 | 17,899 | 69,209 | 21,493 | 69,553 | 13,526 | 43,709 | 6,076 | 6,076 |

| Other higher-skilled | 10,767 | 40,550 | 9,760 | 41,927 | 11,767 | 46,801 | 14,066 | 44,740 | 8,026 | 26,652 | 4,384 | 4,384 |

| Other lower-skilled | 4,885 | 16,419 | 4,669 | 19,976 | 6,081 | 22,753 | 7,391 | 25,483 | 5,428 | 16,882 | 1,649 | 1,649 |

| Other occupations21 | 56 | 349 | 102 | 558 | 103 | 516 | 117 | 536 | 101 | 368 | 47 | 47 |

| Total unique22 persons | 29,291 | 105,647 | 27,493 | 111,833 | 31,339 | 116,781 | 33,918 | 117,996 | 26,653 | 95,086 | 18,772 | 18,772 |

Source: Citizenship & Immigration Canada, RDM, June 8, 2015

Note: The table on temporary residents has been revised to reflect the June 20, 2014 changes to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). The reporting methodology has also been revised to count temporary residents (TR) based on the type of permit held by a TR (effective from the date that the permit was signed). As a result of the changes above, the reports for each permit holder type have been separated by permit type in order to enhance clarity. For further information, please refer to the Facts and Figures 2014 – Immigration overview: Temporary residents overview and the glossary of terms and concepts.

Works Cited

- Conference Board of Canada. Immigrants as Innovators: Boosting Canada’s Global Competitiveness. 2010.

- Science, Technology and Innovation Council. State of the Nation 2014 – Canada’s Science, Technology and Innovation System: Canada’s Innovation Challenges and Opportunities. Ottawa. 2015.

- Ibid, p. 39

- Ibid.

- See the Appendix for a table of data on the Temporary Foreign Worker Program work permit holders by program.

- The LMIA data are displayed elsewhere in this report. These data do not distinguish between LMIAs for high-skilled versus low-skilled positions, and not every positive LMIAs results in the issuance of a work permit.

- Note: it is not a requirement that a job offer be validated with a positive LMIA. In fact, with most of the Express Entry draws having a cut-off of less than 600 points, which shows that LMIAs (which attract 600 points for a candidate) are not a requirement to receive an invitation to apply. The issue is that if a person is not the beneficiary of an LMIA or a provincial/territorial nomination certificate, there is no way to know when or whether a person will be invited to apply for permanent residency. Business and skilled foreign nationals both seek predictability more than anything. Skilled foreign nationals have personal lives and families to consider, and the unpredictability is highly problematic.

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Report on Plans and Priorities 2015-2016. Available at: www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/rpp/2015-2016/index.asp

- Drummond, Don, Evan Capeluck and Matthew Calver. The Key Challenge for Canadian Public Policy: Generating Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth. Centre for the Study of Living Standards. Ottawa. September 2015. p. 161.

- Nakache, Delphine and Leanne Dixon-Perera. Temporary or Transitional? Migrant Workers’ Experiences with Permanent Residence in Canada. IRPP. Montreal. October 2015.

- For details, see the U.K. government’s news release: www.gov.uk/government/news/tech-city-uk-unveils-tech-nation-visascheme

- Levey, Gregory. “A sustainable tech company can’t hire just Canadians.” The Globe and Mail. Sept. 8, 2015.

- The internal bulletin is among the documents in a release package in response to Access to Information Act request number A-2015-00182: Copy of the New Training Manuel (sic) used by Service Canada Employees to Process Labour Market Impact Assessments, available by request at: http://open.canada.ca

- See Table 1 – Employer Conditions in Schedule 2 in the Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, dated July 1, 2015. Available at: http://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2015/2015-07-01/html/sor-dors144-eng.php

- The Canadian Bureau for International Education. “Facts and Figures.” Online at: www.cbie.ca/about-ie/facts-and-figures

- Ibid.

- CBC News. “Canada wants to double its international student body.” Jan. 15, 2014. Online at: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/canada-wants-to-double-its-international-student-body-1.2497819

- CBIE. Ibid.

- World Economic Forum. The Business Case for Migration. 2013.

- Data for 2015 are preliminary estimates and are subject to change. For 2010-2013, these are updated numbers and different from those of Facts and Figures 2014.

- Includes permit holders who hold permits with a not stated occupation and permits with a CIC synthetic occupation that is not included in ESDC’s National Occupational Classification.

- The total unique count may not equal to the sum of permit holders in each program as an individual may hold more than one type of permit over a given period.

The Power to Shape Policy & Of Our Network

Get plugged in.

As Canada’s largest and most influential business association, we are the primary and vital connection between business and the federal government. Wtih our network of over 450 chambers of commerce and boards of trade, representing 200,000 businesses of all sizes, in all sectors of the economy and in all regions, we help shape public policy and decision-making to the benefit of businesses, communities and families across Canada.