Creating a Long-Term Advantage for Ontario

On November 17, the Greater Niagara Chamber of Commerce (GNCC) in partnership with the Ontario Chamber of Commerce (OCC) has released new data that reveals a significant tourism opportunity gap when compared to international growth rates. According to the organization’s report, Closing the Tourism Gap: Creating a Long-Term Advantage for Ontario, Ontario has foregone nearly $16 billion in visitor spending between 2006 and 2012 by not keeping up with global growth trends. While this year has been a strong year for tourism in Ontario, it is important that this recent growth is translated into long-term, sustainable gains in tourism visitation. You can read the report below, or download a PDF version.

ABOUT THE ONTARIO CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

For more than a century, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce (OCC) has been the independent, non-partisan voice of Ontario business. Our mission is to support economic growth in Ontario by defending business priorities at Queen’s Park on behalf of our network’s diverse 60,000 members.

For more than a century, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce (OCC) has been the independent, non-partisan voice of Ontario business. Our mission is to support economic growth in Ontario by defending business priorities at Queen’s Park on behalf of our network’s diverse 60,000 members.

From innovative SMEs to established multi-national corporations and industry associations, the OCC is committed to working with our members to improve business competitiveness across all sectors. We represent local chambers

of commerce and boards of trade in over 135 communities across Ontario, steering public policy conversations provincially and within local communities. Through our focused programs and services, we enable companies to grow at home and in export markets.

The OCC provides exclusive support, networking opportunities, and access to innovative insight and analysis for our members. Through our export programs, we have approved over 1,300 applications, and companies have reported results of over $250 million in export sales.

The OCC is Ontario’s business advocate.

Author: Scott Boutilier, Senior Policy Analyst

ISBN: 978-1-928052-36-4

© Copyright 2016. Ontario Chamber of Commerce. All Rights Reserved.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A Letter from the President & CEO

Introduction

The Economic Impact of Tourism in Ontario

The Challenge: Ontario’s Tourism Gap

Comparing International and Provincial Tourism Trends

Defining the Tourism Gap

Closing the Tourism Gap

Engage in Strategic and Evidence-based Planning

Improve the Tourism Business Environment

Enhance Visitor Access to Tourism Attractions

Support Tourism Marketing

Conclusion

Appendix: A Note on Defining ‘Tourism’

Works Cited

A LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CEO

Ontario’s tourism industry plays a vital role in supporting the growth of the province’s economy. Tourism businesses and other members of the industry support over 360,000 jobs and generate over $25 billion in GDP, but perhaps the industry’s greater value is its widespread contribution to local economies throughout Ontario. Like the province’s network of local chambers of commerce and boards of trade, the tourism industry has roots in most communities across the province. A thriving tourism industry really does translate into a thriving Ontario.

Following a decade of significant decline, Canada’s growth rate in attracting international visitors has recently begun to improve. So far, 2016 has been a very good year for tourism in Canada, with overnight visits up 10 percent from this time last year. While this growth is encouraging, it should also be cause for reflection. Until recently, our province was experiencing relatively little growth in the number of visitors each year, and current visitation numbers remain below historical levels. Meanwhile, the number of visitors internationally has increased steadily, resulting in a widening tourism gap between our province and international tourism trends.

It is essential that Ontario’s tourism businesses, organizations, as well as government take active steps to ensure that this year’s boost in tourism is sustained over the long-term. To achieve real growth in our tourism industry, we must tap into growth in the international tourism market. This requires a more concerted effort to attract international visitors and enhanced coordination amongst federal, provincial, and local tourism marketing organizations. It also means developing the suite of products and services that meet the demand of today’s tourists. In this report, we make a number of recommendations to help the tourism industry and government accomplish these objectives.

Later this year, the government is expected to release its Strategic Framework for Tourism in Ontario, which will set out a long-term vision for the industry. We hope that the recommendations contained in this report help support and guide the efforts of government as it implements its vision for the tourism industry. To be successful, it is also essential that the government integrate its long-term tourism strategy with the Ontario Culture Strategy, the Sport Plan, and broader economic development strategies. Finally, sustained engagement with the tourism industry is critical.

Ontario has many of the ingredients it needs to be a premier global tourism destination. By working collectively, tourism businesses, associations and organizations, as well as government can attain consistent growth in international tourism visitation and drive economic prosperity throughout the province.

Allan O’Dette

President and CEO

Ontario Chamber of Commerce

Introduction

With a thriving arts and culture sector, natural assets, globally-renowned cities, and a positive international reputation, Ontario has the potential to be a larger tourist destination than it is today. The industry is already a vital component of the economy. Tourism activitiesa added over $25 billion to the province’s GDP and supported over 360,000 jobs in 2013. Unlike other economic contributors, tourism has roots in all communities across Ontario, and supports many different sectors of the economy. Actions that reinforce the growth of the tourism industry therefore have the potential to generate economic rewards for the entire province.

With a thriving arts and culture sector, natural assets, globally-renowned cities, and a positive international reputation, Ontario has the potential to be a larger tourist destination than it is today. The industry is already a vital component of the economy. Tourism activitiesa added over $25 billion to the province’s GDP and supported over 360,000 jobs in 2013. Unlike other economic contributors, tourism has roots in all communities across Ontario, and supports many different sectors of the economy. Actions that reinforce the growth of the tourism industry therefore have the potential to generate economic rewards for the entire province.

The tourism industry is one of the fastest growing sectors of the global economy, comprising approximately 9 percent of global GDP and supporting one in 11 jobs. The industry’s growth has been resilient in the face of global economic and geopolitical uncertainty, and is likely to continue: according to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), international tourist arrivals globally are expected to grow by 3.3 percent per year until 2030.

But against this backdrop of global growth, tourism performance in the province, especially international tourism, has declined in relative terms. Some of this decline can be attributed to factors beyond the province’s control—currency changes, heightened security, and financial crises, for example. At the same time, the global market has become increasingly competitive. Many emerging economies have effectively positioned tourism as a driver of economic development, while Ontario’s traditional competitors have taken significant steps to enhance their attractiveness as tourism destinations. Based on average global growth in tourism visitation, Ontario has foregone $16 billion in visitor spending since 2005. The province’s travel deficit exceeded $8 billion in 2013.

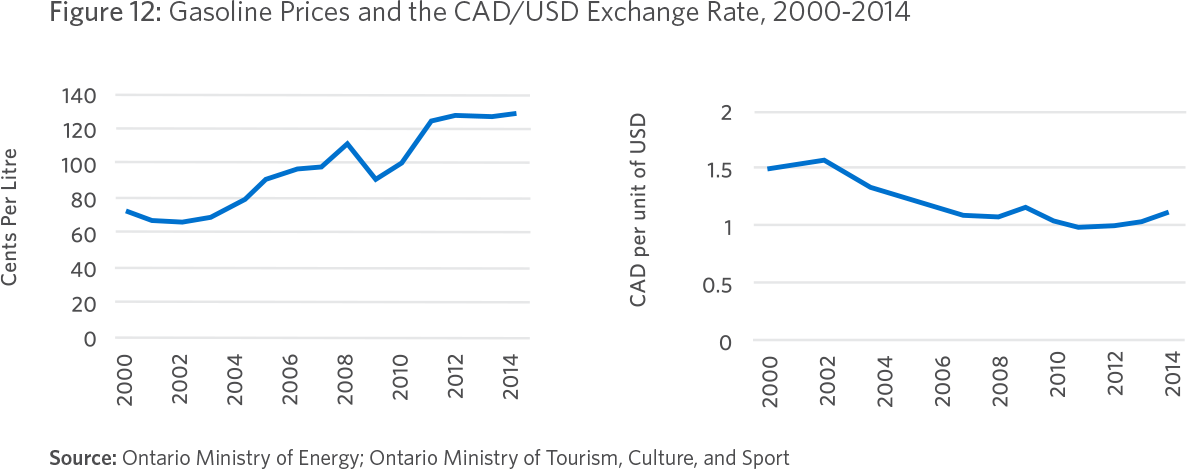

Preliminary visitation data for 2016 hint at a recovery. A weaker Canadian dollar and relatively stable gas prices have set the province’s tourism community up for success this year. But it is important that these temporary tourism gains not mask underlying sector vulnerabilities. Conscious efforts must be made to create a sector that is sustainable over the long term.

In this report, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce (OCC) examines the state of Ontario’s tourism industry and seeks to answer the question: What steps can Ontario take to create a long-term tourism advantage? To do so, we first present the economic contribution that the tourism industry makes to Ontario’s economy. Next, we examine the tourism industry’s growth trends within Ontario and compare them to the global reality. Finally, in consultation with our membership and the broader tourism community, we highlight key actions that the Government of Ontario and industry partners need to take to boost the long-term competitiveness of the tourism industry and generate sustainable demand for tourism in Ontario.

a See Appendix for a note on defining tourism.

The Economic Impact of Tourism in Ontario

Tourism is an important driver of economic activity in Ontario. The industry is a key source of employment and international exports, and it also unique in its diversity of impact by region and sector.1

ECONOMIC ACTIVITY

ECONOMIC ACTIVITY

In 2013, tourism receipts in the province exceeded $28 billion, adding over $25 billion to provincial GDP.2 Based on 2012 data, the tourism industry comprised 3.7 percent of Ontario’s total real GDP, making it the 16th largest industry contributor to the province’s economy.

EMPLOYMENT

The tourism industry is also a significant creator of jobs in Ontario, supporting over 360,000 jobs in 2013.3 In 2012, the industry accounted for 5.2 percent of provincial employment, making it the 14th largest employer in the province.

In 2012, employees aged 15 to 24 comprised 36 percent of the tourism industry workforce, compared to 15 percent of the Ontario workforce as a whole. The tourism industry workforce also includes a higher proportion of summer students relative to the rest of the economy.

EXPORTS

Because tourism involves non-Ontarians purchasing Ontario products and services, this spending is considered a form of export for Ontario. In 2012, the tourism industry generated $6.2 billion in exports, ranking as the ninth largest international export industry in the province.

DIVERSITY OF IMPACT

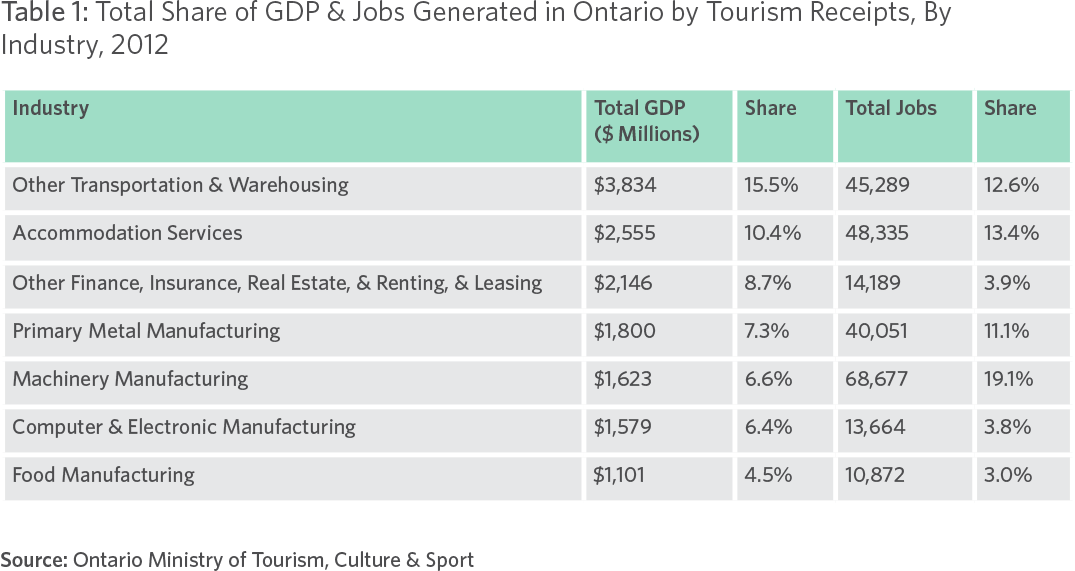

Probably the most unique feature of tourism is its widespread impact on Ontario’s economy. First, tourism supports economic activity in a wide array of sectors. As the table below demonstrates, tourism GDP is generated by a number of industries in the province, most notably in the transportation industry (17.4 percent of tourism GDP) and accommodation services (10.4 percent). At the same time, jobs associated with tourism receipts occur in a number of different industries, including 19.1 percent of jobs in food services and 14.9 percent in transportation.

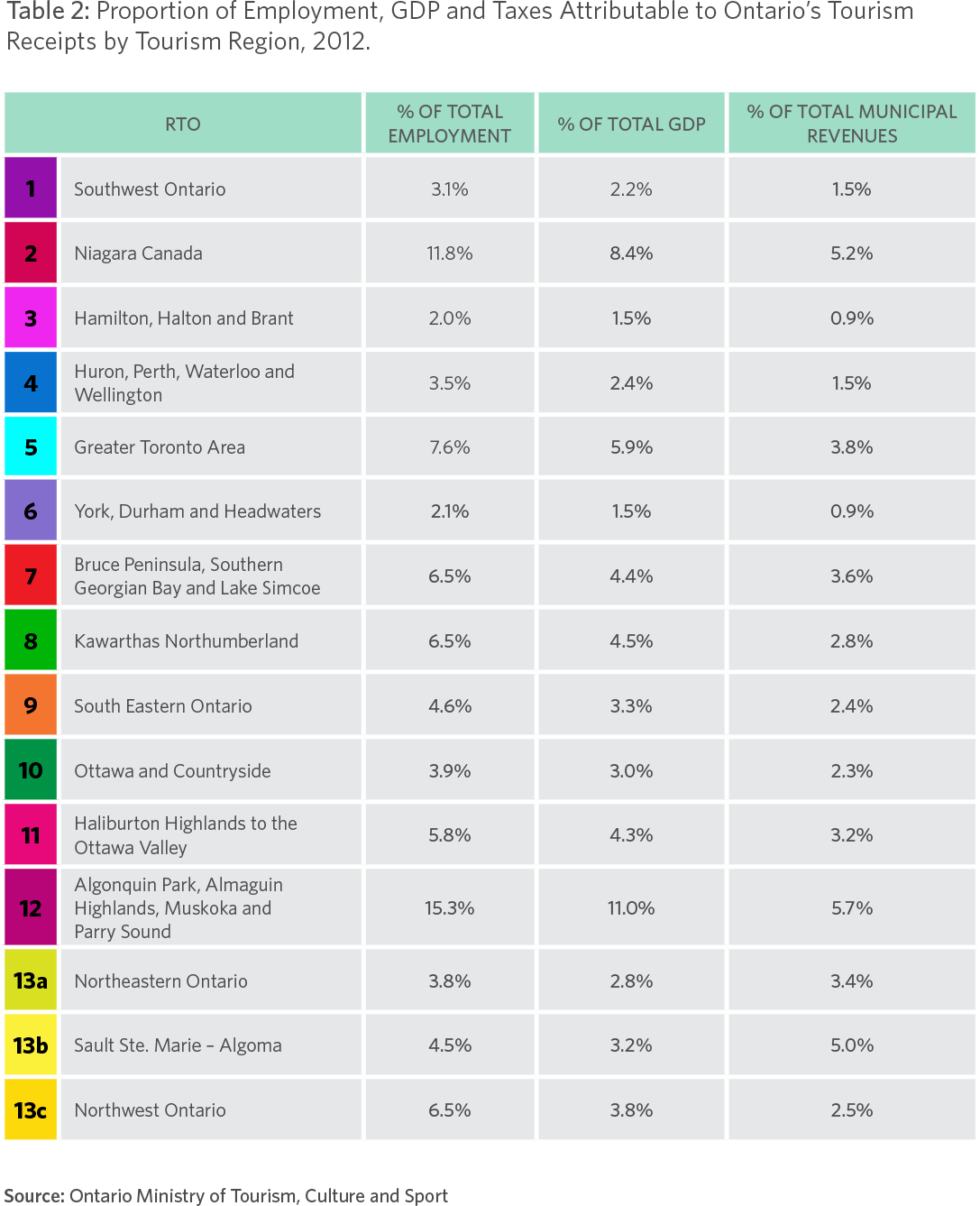

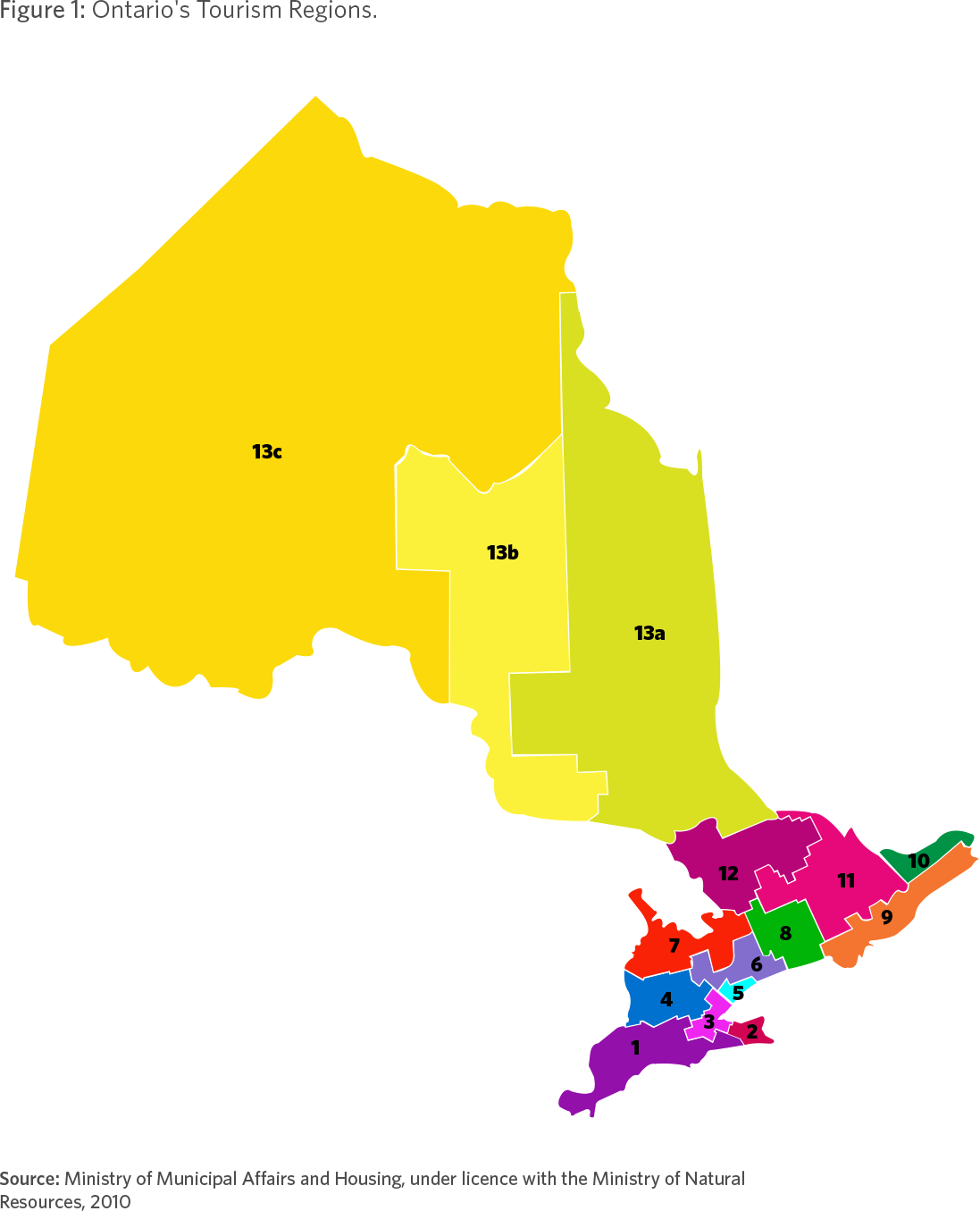

Second, the tourism industry supports economic activity in all regions of Ontario. As demonstrated by the table below, tourism comprises at least 3 percent of GDP for most regions, as well as 4 percent of total employment. For some regions, such as Region 2 (Niagara) and Region 12 (Algonquin Park, Almaguin Highlands, Muskoka and Parry Sound), tourism is of considerable economic importance.

Note: Please see below to cross-reference with the Ontario’s Tourism Regions map.

The Challenge: Ontario’s Tourism Gap

In recent years, the tourism industry has experienced remarkable growth and is now one of the largest and fastest growing sectors in the global economy.4 While Ontario’s tourism industry is an important contributor to the economy, its performance in recent years has not kept pace with global trends. This has created a noticeable divergence, or ‘tourism gap’, between global tourism growth and the province’s tourism visitation. This gap is a considerable lost opportunity for the province. In this section of the report, we characterize Ontario’s tourism gap in more detail, based on the most current publicly available data.

In recent years, the tourism industry has experienced remarkable growth and is now one of the largest and fastest growing sectors in the global economy.4 While Ontario’s tourism industry is an important contributor to the economy, its performance in recent years has not kept pace with global trends. This has created a noticeable divergence, or ‘tourism gap’, between global tourism growth and the province’s tourism visitation. This gap is a considerable lost opportunity for the province. In this section of the report, we characterize Ontario’s tourism gap in more detail, based on the most current publicly available data.

COMPARING INTERNATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL TOURISM TRENDS

According to the UNWTO, tourism is one of the fastest growing sectors of the global economy. Currently, the industry comprises 9 percent of global GDP and is responsible for one in 11 jobs. The industry also generates US$1.5 trillion in exports, or 6 percent of global exports and 30 percent of global services exports.5

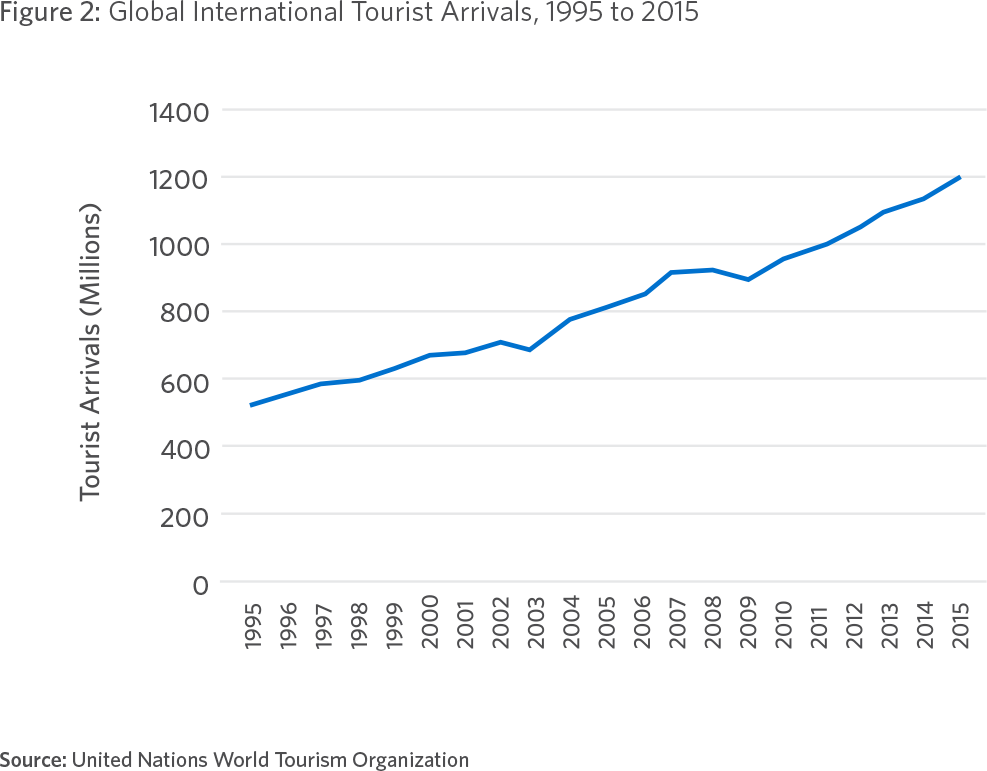

This significant contribution to the global economy is the result of decades of sustained growth. From 1950 to 2015, the number of international tourist arrivals has increased from 25 million to 1.2 billion, resulting in an increase of global tourism receipts from US$2 billion to US$1.3 trillion in 2014 (Figure 2).6,7

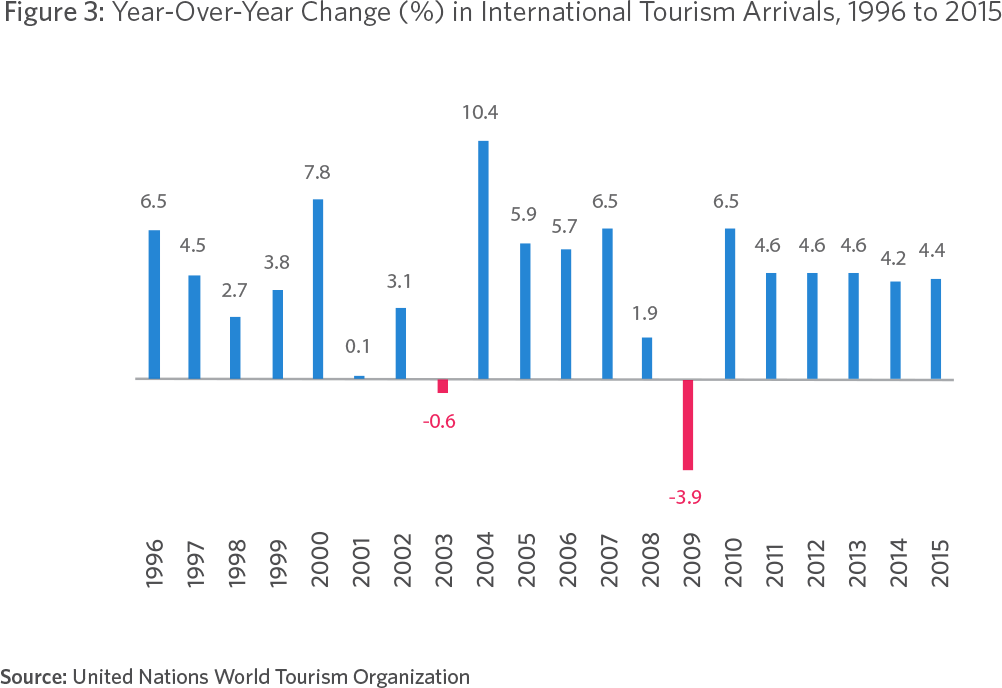

Global tourism growth has also demonstrated resiliency to recent economic and geopolitical uncertainty, as well as an ability to quickly recover from financial, health, and other crises. In particular, annual growth in international tourism arrivals has been remarkably consistent following the 2007-08 financial crisis, a period in which the global economy has experienced both uncertainty and sluggish growth (Figure 3). Indeed, the annual growth in tourism arrivals has outpaced average global GDP growth over this period.8

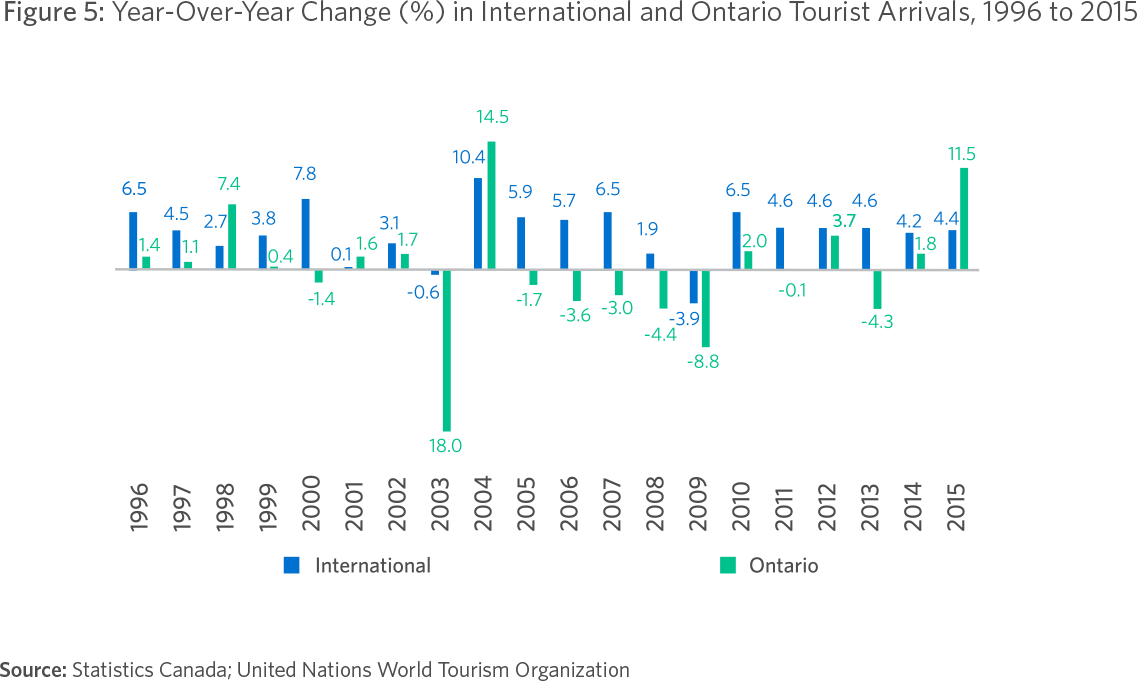

In Ontario, tourism trends over the same period have been remarkably different. Even as global tourism visitation increased, the number of non-resident tourists, or overnight visitors, visiting Ontario declined from a peak of 9.8 million arrivals in 2002 to 8.4 million in 2015 (Figure 4). For much of that period, Ontario’s year-over-year visitation numbers were unable to match the magnitude of global growth (Figure 5).

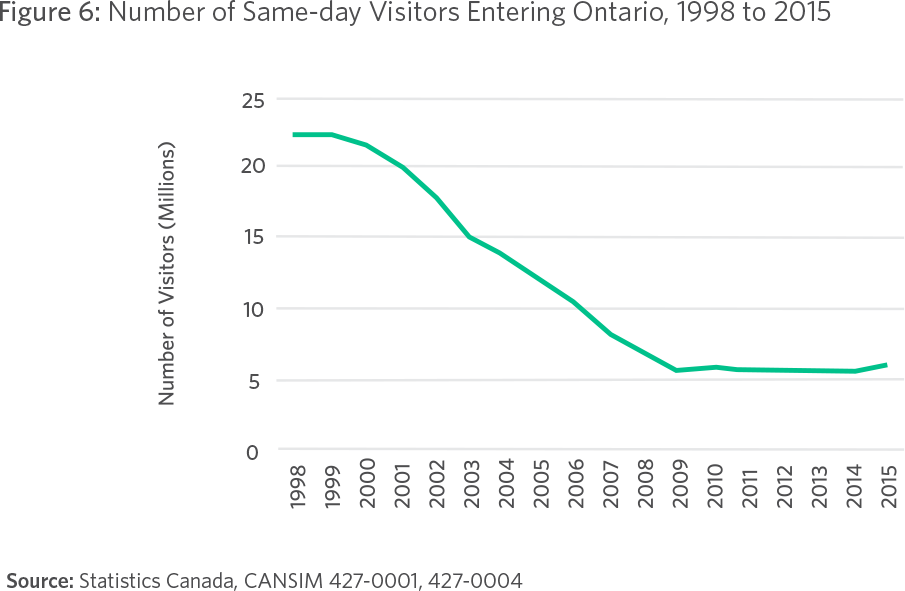

The number of same-day visitors to Ontario declined even more precipitously over the same period (Figure 6). This decline was driven mostly by a 75 percent drop in American visitors.9

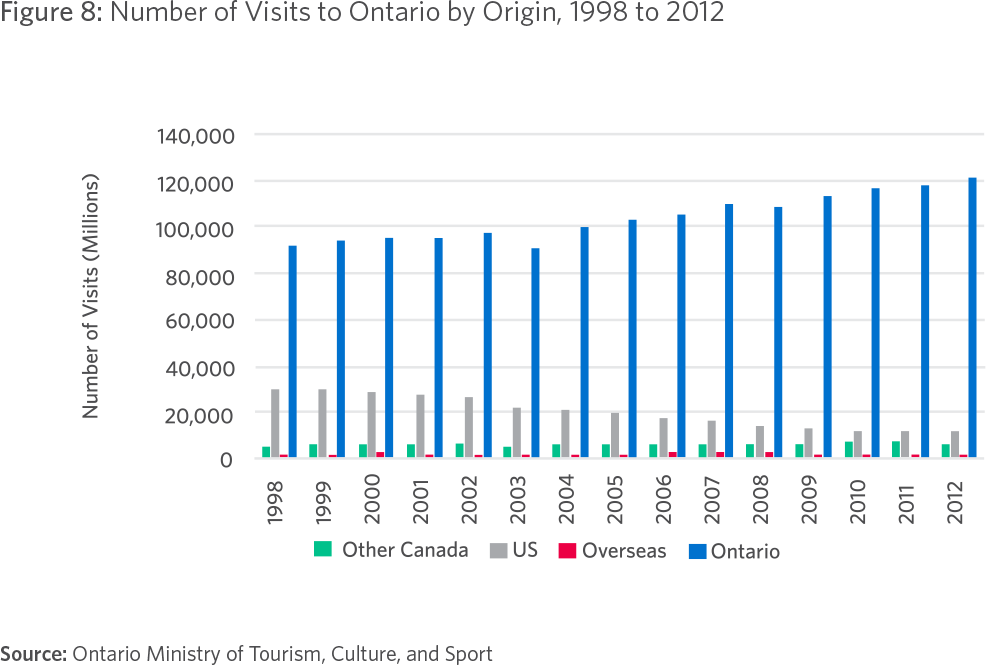

Despite these negative international visitor trends, Ontario’s tourism numbers are positive when viewed in aggregate. For example, from 1998 to 2012, total tourist visits to Ontario increased by 11 million, resulting in growth in nominal tourism receipts from $19 billion to $28 billion over the same period (Figure 7). This is due to the strength of the province’s domestic tourism sector, which makes up a large and increasing proportion of tourism visits (Figure 8).

Even with the growth of domestic visitation, the scale of Ontario tourism’s growth has not kept pace with global growth. It has also not kept pace with the growth of Ontario’s economy: the direct industry contribution to provincial GDP declined from 1.9 percent to 1.6 percent between 2000 and 2012.10

DEFINING THE TOURISM GAP

As illustrated, Ontario has not been able to attract visitors at the same pace as tourist visitation has increased globally. While tourism is an important contributor to the province’s economy, the data suggest that Ontario has missed an opportunity to capitalize on growing global tourism demand to drive even greater economic growth. This missed opportunity, or difference between potential and actual tourism visitation growth, can be characterized as the tourism gap.

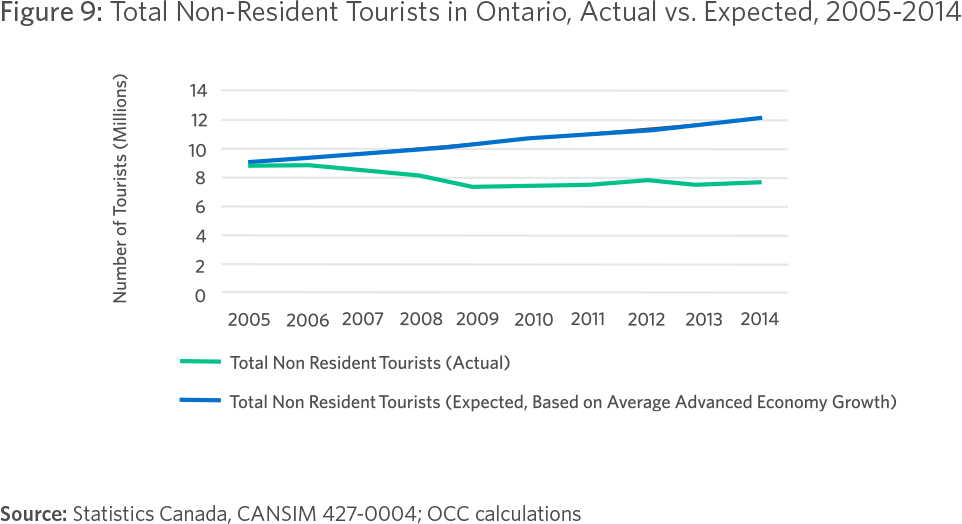

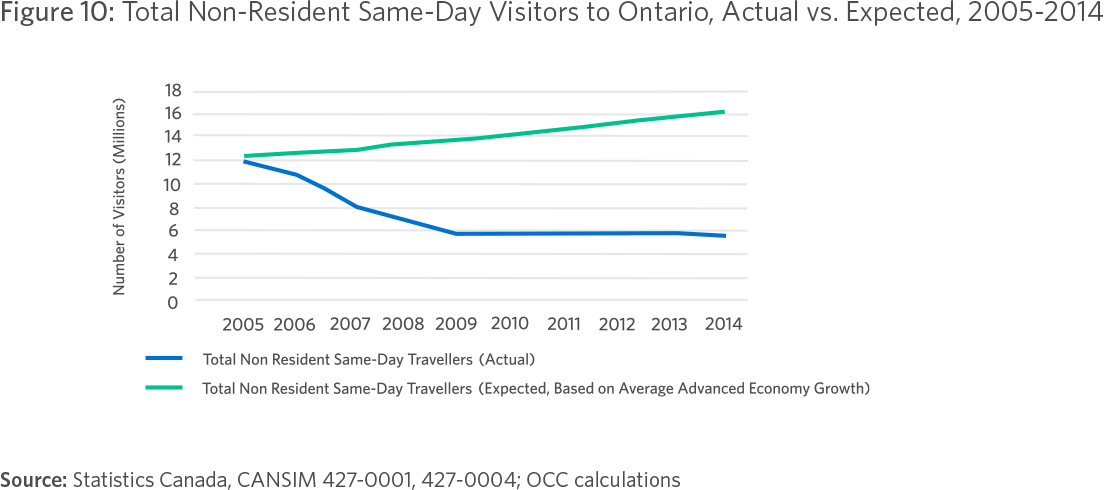

To better illustrate this tourism gap, we calculated the difference between Ontario’s actual and potential tourism growth based on the average growth in visitation by advanced economies since 2005 (or 3.2 percent).11 We then used average visitor spending data in Ontario over the same period to calculate foregone tourism spending in Ontario by failing to keep pace with global growth.

As shown in Figures 9 and 10, the cumulative divergence of Ontario non-resident tourism numbers from international growth trends suggest a large gap between potential and actual visitation, both for tourists as well as same-day travellers. For the sake of simplicity, we have applied the average advanced economy growth rate to same-day travellers.

Based on the average spend per overnight and same-day traveller to Ontario in each year, the tourism gap represents $16 billion in foregone spending from 2006 to 2012 alone. In other words, if the province had kept pace with global tourism growth, visitors to Ontario from abroad would have spent $16 billion more during this period.

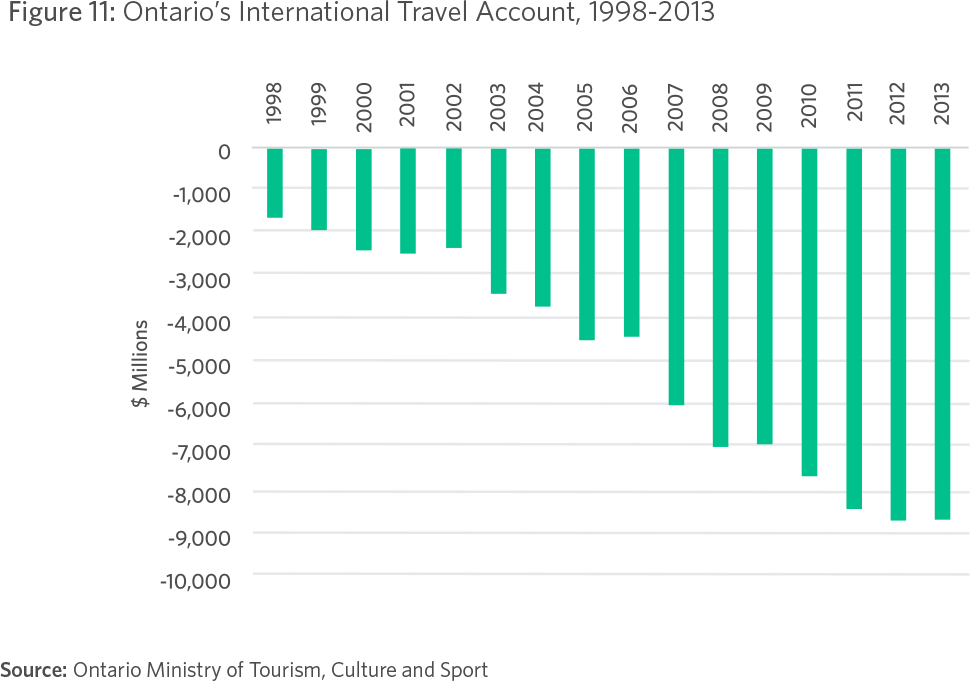

Ontario’s tourism gap has contributed to a growing de cit in the province’s international travel account, meaning that Ontarians are spending more abroad than international visitors are spending in Ontario. This de cit has increased from $1.6 billion in 1998 to $8.6 billion in 2013 (Figure 11).

As illustrated above, Ontario has diverged significantly from the incredible growth experienced by the global tourism industry. That divergence has created a large tourism gap, amounting to $16 billion in foregone visitor spending between 2006 and 2012.

Indications for 2016 suggest that external factors are shifting in Ontario’s favour: Canada’s low-valued dollar is expected to attract more international visitors, particularly from the U.S., while also encouraging more Ontarians to vacation within the province.12 Lower than usual gas prices are also expected to increase land travel.13 The province’s challenge, and a critical objective of its upcoming strategic framework, will be to ensure that these gains are sustained over the long-term. In the next section, we identify actions that the government and industry can be taking in key areas to help achieve this objective.

Closing The Tourism Gap

International projections suggest that the global tourism industry will continue to grow in the coming years. According to the UNWTO, international tourist arrivals are expected to increase by 3.3 percent per year between 2010 and 2030, reaching 1.8 billion in total arrivals by 2030.14 Ontario has a critical window of opportunity to tap into this global growth to boost its own industry’s contribution to the economy.

International projections suggest that the global tourism industry will continue to grow in the coming years. According to the UNWTO, international tourist arrivals are expected to increase by 3.3 percent per year between 2010 and 2030, reaching 1.8 billion in total arrivals by 2030.14 Ontario has a critical window of opportunity to tap into this global growth to boost its own industry’s contribution to the economy.

To create long-term sustainable growth in the province’s tourism industry, both government and industry must act together to close the tourism gap. Isolating the specific drivers of Ontario’s tourism gap is a difficult task, as many different factors have contributed to provincial tourism visitation trends.

External factors have significantly impacted visitation to Ontario. For example, the CAD/USD exchange rate has experienced significant volatility over the past decade-and-a-half, and the strength of the Canadian dollar was likely a determining factor in the decline in international visitation from the U.S. Gasoline prices also rose significantly, increasing the cost of travel. During the same period, other shifting external forces—border security issues, newly introduced passport requirements, health scares, and financial crises—also likely impacted tourism visitation.15

Meanwhile, the global tourism landscape also became more competitive. From 2000 to 2014, as visitation to Ontario and Canada declined, traditional tourism destinations like France, the U.S., and Spain strengthened their annual visitation numbers. At less than two percent, tourism’s contribution to Canada’s GDP fell to well below the OECD average of 4.1 percent by 2014.16 Meanwhile, emerging countries also sought to leverage tourism as an economic development opportunity. Countries like Malaysia and Thailand saw strong increases in visitation and moved ahead of Canada on international rankings.17,18

To suggest that tourism visitation is solely a product of these and other external factors, however, would be a mistake. From the perspective of the OCC’s membership, there exist gaps in Ontario’s approach to tourism growth that, if remedied, could help to increase the competitiveness of the province as a global tourism destination.

Based on conversations with our membership and the broader tourism community, we have identified a select number of domestic actions that, if taken, may help to close the tourism gap. In particular, after the introduction of its long-term strategy, we urge the government to consider two short-term measures to integrate the tourism industry into its ongoing initiatives: add tourism to the Red Tape Challenge and create a Tourism Industry Table as part of its highly skilled workforce plan. This set of recommendations is not exhaustive, and stronger data would have increased the precision of these recommendations. But, they do present opportunities to address some of the industry’s major challenges, from the perspective of the business community, and build the foundation of a long-term tourism advantage for Ontario.

ENGAGE IN STRATEGIC AND EVIDENCE-BASED PLANNING

Tourism is a complex and multi-faceted industry, encapsulating organizations from many sectors and interacting with decision makers across government. To be successful, policy development in this industry demands an integrated approach “across many government departments, at different levels of government and with the close involvement of the private sector.”19 This is why jurisdictions are increasingly employing long-term, whole- of-government strategies to address challenges faced by the tourism industry and create sustainable tourism development.20

In recent years, Ontario has lacked a clear, strategic vision for the tourism industry with explicit growth targets. The 2009 Discovering Ontario report, the result of a large-scale industry review, suggested a goal of doubling provincial tourism receipts by 2020.21 However, that target was never officially adopted, nor was an official strategy developed to meet that goal. This has made it difficult for government, tourism organizations, businesses, and communities to align their industry growth efforts.22

In part, an insufficient evidence base has hindered the development of strategic tourism planning. While Ontario’s Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport (MTCS) publicly releases updates on a range of tourism indicators, a consensus exists that publicly available tourism data do not meet the needs of the industry as a whole. specifically, the timeliness of tourism data is an overriding concern. In Ontario, the most current economic data (based on visitor spending) are from 2013. For the government, communities, and tourism businesses currently planning for the 2017 tourism season and beyond, three-year-old data are inadequate.

Delivering on a province-wide strategic plan will require the cooperation and coordination of different tourism organizations and industry groups. In Ontario, many organizations at various levels of engagement (national, federal, municipal) are involved in tourism activities, from product creation to skills development to marketing. OCC members have expressed concern about whether the activities of these groups are being sufficiently coordinated to reduce overlap and maximize the impact of scarce tourism dollars. Businesses are particularly concerned about tourism marketing and whether competition between tourism brands within Ontario is diluting the provincial tourism brand.

Recommendation 1: Develop a government-wide Ontario tourism strategy with measurable targets

If Ontario is to successfully build a sustainable and globally competitive tourism industry, it is essential that the government develop a long-term tourism strategy. Encouragingly, the Government of Ontario is already taking this essential first step: throughout 2016, MTCS has been leading consultations towards the development of the Strategic Framework for Tourism in Ontario. The OCC fully supports the government’s efforts to create this guiding document, and look forward to its release later this year.

To direct and prioritize government and industry efforts, however, the government’s framework must include specific and measurable goals for industry growth, as well as a timeline to achieve those goals (a practice adopted by many other jurisdictions). To do so, the government must clearly define the type of growth it wants to achieve: is it driving visitation to all regions, increasing international visitation, maximizing visitor spending, or something else?

On this issue, the OCC agrees with the Tourism Industry Association of Ontario (TIAO): to create sustainable, long-term growth in the tourism industry in Ontario and maximize potential visitor spending, the province’s tourism strategy should emphasize the attraction of non-resident visitors to Ontario.23 At the very least, the government should aim to keep pace with global growth in international tourism visitation, which the UNWTO estimates at 3.3 percent per year until 2030. Importantly, this approach is not incompatible with supporting domestic tourism growth; in fact, making Ontario a more competitive tourism destination internationally will undoubtedly increase the attractiveness of the province as a destination for Ontarians as well.

EXAMPLES OF MEASURABLE OBJECTIVES IN OTHER JURISDICTIONS

British Columbia

Gaining the Edge 2015-18

Target: 5 percent annual revenue growth for the tourism industry

Alberta

Alberta’s Tourism Framework

Target: tourism is a $10.3 billion industry by 2020

Ireland

People, Place, and Policy: Growing Tourism to 2025

Targets: revenue from overseas tourism grow to EUR 5 billion

by 2025; 250 000 employed in tourism; 10 million overseas visits to Ireland

Australia

Tourism 2020

Target: achieve more than AUD 115 billion in overnight spending by 2020

Recommendation 2: Work with relevant partners to improve the timeliness of tourism data dissemination, specifically related to visitor spending, as well as the scope of available tourism data

In Ontario’s Tourism Action Plan, MTCS highlighted the need to improve tourism data quality and availability. The OCC strongly supports the government’s decision to include this item in the action plan and encourages the government to work with relevant partners at the municipal, provincial, and federal level to improve the timeliness of tourism data, specifically related to visitor spending. In the interim, there may be opportunities to better leverage existing data. The government, in partnership with industry, should investigate alternative methods of generating tourism economic data by leveraging more frequently updated and accessible data sets, such as the Consumer Price Index or employment.

Government and industry should also work to expand the scope of tourism data available in Ontario. The Ontario Tourism Marketing Partnership Corporation (OTMPC) has recently undertaken work to gain a better understanding of the tourism market in Ontario, including detailed investigations of the types of visitors that the province attracts. From an industry perspective, additional and more regular market investigations are needed. For example, tracking visitor flows, or how visitors move within the province, can inform both product development decisions and infrastructure investment decisions to improve connectivity where large visitor flows exist. In 2007, New Zealand introduced a tourism flows model to spatially represent the dynamics of tourism in the country and inform policy, planning, and resource allocation activities.24 Developing a similar model in Ontario would create a deeper understanding of the market.

Recommendation 3: Work with industry to more clearly define the roles and responsibilities of the province’s tourism organizations

To reduce overlap in tourism activities and maximize the province’s scarce tourism dollars, the government should work with industry players to refine the roles of relevant tourism organizations. From a marketing perspective, the government should consider focusing the OTMPC’s efforts on attracting international visitors and reduce its in-province marketing activities.25 It is also important that OTMPC continues to work with Destination Canada to leverage national marketing activities to enhance the reach of Ontario’s international marketing efforts. Enhanced coordination among the province’s tourism organizations will be essential to delivering on the province’s forthcoming tourism strategy.

IMPROVE THE TOURISM BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

Improving Ontario’s tourism competitiveness requires a dynamic, entrepreneurial, and innovative business community that can create new products and experiences, provide high quality service, and adapt to visitor expectations. In turn, tourism businesses require an operating environment that allows them to do so.

Consultations with OCC members revealed that tourism operators are struggling with the cost of doing business in Ontario. In 2012, Ontario was home to nearly 151,000 tourism-related establishments, over 90 percent of which had less than 20 employees.26 Recent research by the OCC and other organizations has found that small businesses in Ontario are facing a number of obstacles to success, including high input costs and a skills gap.27

National evidence suggests that SMEs in the tourism industry may be facing these challenges more acutely than SMEs in other sectors of the economy. According to Statistics Canada’s Survey on Financing and Growth of SMEs, 81 percent of tourism SMEs identified the rising costs of inputs as a perceived obstacle to growth, compared with 61 percent of other SMEs. At the same time, 45 percent of tourism SMEs identified government regulation as an obstacle to their growth, as opposed to 32 percent of other SMEs.28 One reason for this may be the breadth of tourism as an industry, which means that tourism establishments in Ontario are regulated by a number of different pieces of legislation, housed in a number of different Ministries.

Tourism SMEs are also experiencing greater difficulty accessing the financing they need to invest in their business. In the same survey, 22 percent of tourism SMEs identified accessing financing as a barrier to growth, compared with 16 percent of other SMEs.29

The OCC also heard that labour shortages are a challenge for tourism operators, which this year’s growth in tourism visitation has more acutely exposed. In 2012, Tourism HR Canada estimated that, by 2030, labour shortages in Ontario’s tourism industry could be expected to exceed 88,000 full-year jobs.30 Already, over 40 percent of tourism SMEs identify “shortage of labour” as an obstacle to growth, and over 50 percent experience issues recruiting and retaining employees.31 Ontario’s tourism industry has long recognized the threat of a labour shortage—an issue that not only impacts businesses’ ability to operate, but our competitiveness as a tourism destination. When visitors are underserved, or serviced by under-skilled employees, the risk of a bad experience increases.

These data suggest that, in order to successfully foster industry growth, a focused effort to improve the business environment for Ontario’s tourism businesses is needed.

Recommendation 4: Work with tourism operators to reduce regulatory and cost burdens, and add tourism to the Red Tape Challenge

In Ontario’s Tourism Action Plan, MTCS committed to working “across government to improve the regulatory environment for the tourism sector,” and intends to hold focused discussions with industry.32 To broaden the scope of these discussions to reflect the cross-ministerial nature of tourism regulation, the OCC encourages government to add “tourism” to the list of target sectors involved in its Red Tape Challenge with a clear consultation timeline. While the Challenge does involve a diversity of sectors, it does not include large tourism-related sectors like transportation or accommodation.

ONTARIO TOURISM WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2012-2017

In 2012, the Tourism Industry Association of Ontario and the Ontario Tourism Education Corporation released a five-year strategy to address the industry’s incoming labour gap challenges and attract and retain high-quality employees. The strategy highlighted four priority areas, as well as a number of strategic initiatives and implementation timeline, to respond to these challenges:

- Foster an environment of collaboration and coordination

- Develop a high performance workforce

- Focus on workforce attraction and retention

- Enhance information management and research

Recommendation 5: Support industry efforts to address the labour shortage by prioritizing workforce development. The government should establish a Tourism Industry Table as part of its Highly Skilled Workforce Strategy.

In 2012, the Tourism Industry Association of Ontario and Ontario Tourism Education Corporation released a comprehensive workforce development strategy for the province, and have been actively working to implement components of it. There are a number of successful programs under way to access and train previously untapped labour pools and enhance the retention of talent, but much more needs to be done.33 While many of these efforts are succeeding, there is a growing consensus amongst industry stakeholders that the scale and scope of these efforts will not be enough to fully address the labour shortage. Investments to address tourism labour issues are relatively small, and the fragmentation of workforce development initiatives amongst a wide array of partners may have led to an inefficient use of scarce resources. At the same time, industry participants worry about how a lack of management capacity among tourism businesses could harm the sustainability of the province’s industry.

In addition to recognizing the efforts of the industry, as outlined in Ontario’s Tourism Action Plan, the OCC recommends that the government place greater emphasis on workforce development in the tourism industry as a broader economic priority. In its final report, the Highly Skilled Workforce Expert Panel recommended the creation of a Planning and Partnership Table (PPT) responsible for “driving change and developing actionable solutions related to skills, talent development and experiential learning opportunities.” In turn, the PPT will be supported by a series of Industry Tables based on growth sectors or regions. We recommend that a Tourism Industry Table be created under the PPT to ensure that the industry’s workforce challenges are incorporated into the province’s broader skills strategy.

ENHANCE VISITOR ACCESS TO TOURISM ATTRACTIONS

For a destination to be competitive, it is essential that its attractions are accessible to visitors. OCC members and other tourism industry stakeholders have consistently identified access as a key area of improvement for Ontario. specifically, the province’s transportation and transit infrastructure does not effectively connect different destinations. Other assets meant to guide visitors, like information centres and wayfinding materials, are also insufficient. For tourism businesses, a lack of sufficient connectivity to transportation infrastructure also creates a human capital problem, particularly for younger workers that may rely on public transit more than other demographic groups.34

The cost of travel, and especially air travel, also reduces the accessibility of attractions in Ontario. Given the relative isolation of Ontario from other markets, and the distance that visitors have to travel to different attractions within the province, air travel is an important mode of access. While Canada benefits from world- class airport infrastructure, it is also one of the most expensive places to fly.35 This is because air travellers in Canada pay a greater proportion of the associated costs of travel compared with other jurisdictions.36,37 The World Economic Forum’s latest Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report ranks Canada 130 out of 141 countries in terms of price competitiveness, mainly due to ticket taxes and airport charges.

Finally, as the government develops a forward-looking tourism strategy, it is important to consider evolving consumer preferences about how visitors want to access tourism destinations. In particular, visitors around the world are increasingly employing sharing economy services as their preferred method of facilitating travel experiences. Globally, revenue from sharing economy companies is expected to grow to $335 billion by 2025, and the OECD predicts that much of this growth will be in the tourism sector.38,39 Leveraging the sharing economy—the provision of goods or services on a short- term basis via peer-to-peer platforms—is a critical tool to both expand tourism and provide new visitor options in Ontario.40 If effectively integrated into Ontario’s tourism strategy, the sharing economy is expected to generate significant economic benefits for the province and the tourism sector.

Recommendation 6: Incorporate tourism considerations into provincial infrastructure investments

Ontario’s infrastructure plan, totaling $160 billion over the next 12 years, as well as the federal government’s infrastructure funding commitments are an opportunity to improve visitor access to Ontario’s tourism offerings.41 Recently, the OCC has encouraged governments to prioritize investments in trade-enabling infrastructure investments that ensure long-term economic and productivity gains for the province. As an important source of export for Ontario, generating $6.2 billion in 2012, the government should view investments that enhance access to tourism attractions with similar economic potential. As discussed above, investments that enhance the connectivity of tourism offerings, including transportation, transit, and wayfinding infrastructure are particularly important. As such, we encourage the government to incorporate tourism access as a key consideration as it moves ahead with critical infrastructure investments. specifically, it should bring together tourism associations and organizations to identify and prioritize tourism infrastructure projects.

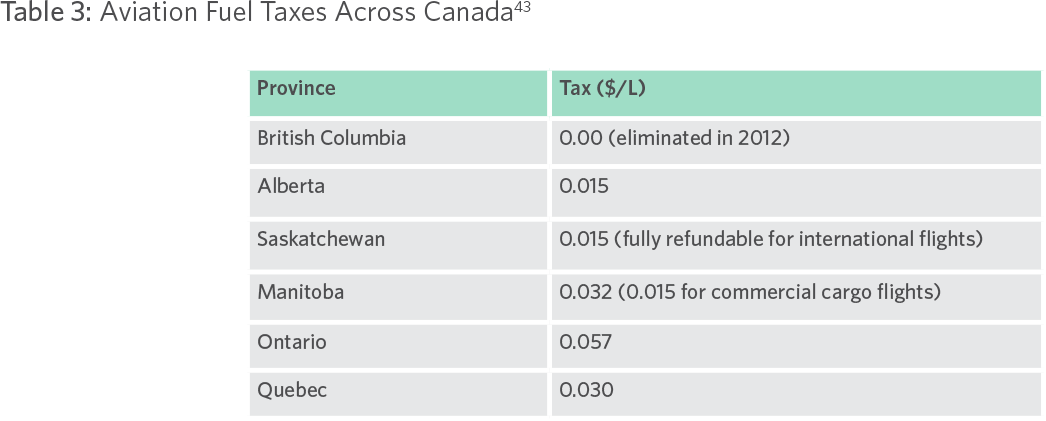

Recommendation 7: Improve Ontario’s air travel cost competitiveness by reducing the aviation fuel tax

Since 2014, Ontario’s aviation fuel tax has increased by nearly 150 percent, making it the highest in Canada. This decision has increased the financial barrier to access many of Ontario’s attractions, particularly in northern and remote communities in Ontario, where other forms of travel may be infeasible for visitors. It has also made the province an outlier within Canada, where other provinces and territories have maintained low tax rates or reduced them (Table 3). Recent studies from the National Airlines Council of Canada have outlined the economic and tourism benefits of reducing the aviation fuel tax in Ontario, as well as the economic cost of an increase.42 To increase Ontario’s price competitiveness as a tourism destination, Ontario should consider reducing its aviation fuel tax to, at the very least, align with other jurisdictions within Canada.

Recommendation 8: Leverage the potential of the sharing economy to expand tourism by promoting consistent, easy-to-follow rules across Ontario

The provision of sharing economy services increases access to tourism for the growing pool of international and domestic visitors, who are increasingly interested in localized experiences.44 The sharing economy helps open doors to communities that are non-traditional tourism markets, but which have unique experiences and assets that are in-demand with visitors. By lowering barriers to participating in the tourism economy, the sharing economy can expand the benefits of tourism to a broader group of local businesses in communities across Ontario.

The sharing economy can also help both large and small markets across Ontario better respond to event- based or seasonal tourism opportunities. This includes improving connectivity to tourism attractions where transportation options are limited, or creating additional, elastic accommodation capacity.45 For example, tourism and municipal leaders in Winnipeg worked together with Airbnb to respond to a spike in accommodation demand during the 2015 Grey Cup, while Live Nation has partnered with Uber to meet short term spikes in demand for transportation at music festivals.46,47 This elasticity and on-demand responsiveness is more cost-effective for many communities across the province, when short-term needs may not justify the development of additional long- term tourism infrastructure or services.

Harnessing this opportunity requires provincial leadership to provide greater consistency for Ontarians and visitors participating in the sharing economy. Hard-to-follow rules that differ between communities are confusing and will discourage Ontarians from sharing their assets. Inconsistency in rule-making also reduces visitor options, detracts from the overall quality of visitor experience in Ontario, and fails to leverage an important opportunity to grow international and domestic tourism in Ontario. We encourage the Government of Ontario, through the work of the Sharing Economy Advisory Committee, to set out clear, easy-to-follow rules for key tourism-supporting services in the sharing economy. While we recognize that some flexibility is required to address local conditions, the province should ensure that Ontarians and visitors can expect general consistency in how they can participate in the sharing economy across the province.

SUPPORT TOURISM MARKETING

In a globally competitive environment, effective marketing of the province’s tourism offerings is critical to facilitate increased visitation and industry growth. In Ontario, marketing activities are the responsibility of a number of different organizations. While OTMPC is largely responsible for branding Ontario and marketing out-of- province, with Regional Tourism Organizations (RTOs) and Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) engaged at a more local level, the marketing activities of these organizations often overlap. For example, some RTOs and DMOs actively market their respective regions internationally. As discussed earlier in this report, a clear delineation of specific roles and responsibilities is essential to maximize the impact of the province’s marketing dollars and reduce brand confusion.

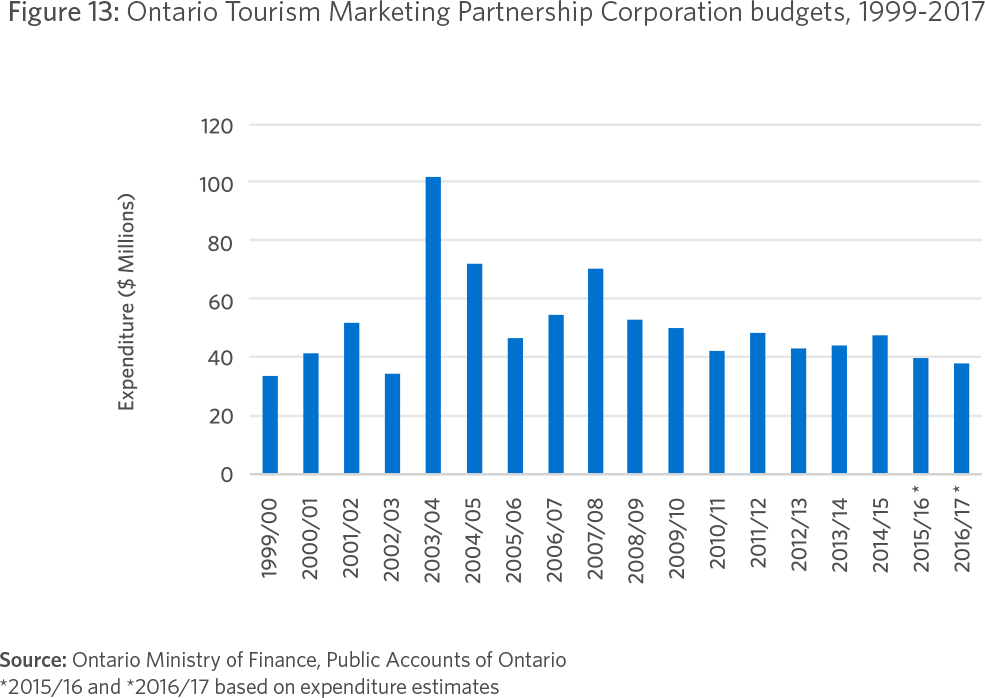

OCC members also worry about the lack of predictability in tourism marketing funding. Since it was established in the late 1990s, the OTMPC’s budget, allocated annually by the government, has experienced considerable volatility (Figure 13). This makes sustained marketing efforts more difficult to plan and execute, particularly as the industry grapples with swings in the value of the Canadian dollar.

Recommendation 9: Create greater consistency and predictability in provincial tourism marketing funding by moving to a multi-year funding model

Creating greater consistency and predictability in marketing funding would help increase the effectiveness of scarce marketing dollars. Currently, the OTMPC and other marketing organizations are provided with funding on an annual basis. A lack of budget certainty over a longer time period reduces their ability to plan for and conduct sustained campaigns in target markets. This is particularly true in the Canadian context, where Ontario’s marketing efforts are being coordinated with Destination Canada and other provincial organizations. A lack of longer-term budget certainty reduces the effectiveness of Ontario’s tourism marketing organizations as a partner in these national efforts to achieve long-term visitation goals. Tourism marketing in Ontario needs to move to a more sustainable funding model. We recommend that the government seek to provide budget certainty on a three-to-five year time horizon for the OTMPC and other marketing organizations to allow for longer-term and sustained marketing campaigns.

Conclusion

Hogg Bay, Ontario, 2016, by Francyne Dufault-Dick, Victoria Harbour, Ontario. Francyne’s photo was the winner of the OCC’s summer photo contest: #PictureOntario. The contest received over 200 photo entries from across Ontario throughout the 2016 summer.

The tourism industry is an important contributor to Ontario’s economy across all regions of the province. While 2016 has been a good year for tourism in Canada, recent improvements in visitation follow a decade of significant decline. As a result, the industry has experienced a widening gap between our province and international tourism trends. With global growth in the industry projected to continue until at least 2030, Ontario has an opportunity to tap into this growth to drive its own economy and close the tourism gap. To do so, however, it must take steps to boost its competitiveness as an international tourism destination. A comprehensive strategy with clear and measurable targets for industry growth is essential to achieving this goal.

The OCC hopes that the recommendations contained in this report, which range from strategic planning to the business environment to marketing, inform the development of Ontario’s long- term tourism strategy. Some of these recommendations will be implemented over the long-term; however, adding tourism to the Red Tape Challenge and creating a Tourism Industry Table are two short-term actions that the government could take to integrate the industry’s priorities into current government initiatives. In addition, while there are areas of overlap between priorities highlighted by government and recommendations in this document, there are also areas of divergence. We hope these priorities are also be reflected in the province’s discussions.

As the Government of Ontario continues to move forward with the development and implementation of a long-term strategy, we encourage it to work with the OCC and members of Ontario’s business community to execute a plan that best reflects the industry’s needs and will best support the future growth of the industry.

Appendix: A Note on Defining Tourism

Most of us have an intuitive sense for what tourism is, but intuition does not always align with international standards or data points. To remain consistent with interjurisdictional best practice and to accurately reflect quantifiable tourism dynamics at a global and local level, this report employs a globally-accepted definition of tourism wherever possible. More specifically, we draw on the work of the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), via its International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics, to apply a hierarchical approach that distinguishes tourism from other travel-related activities.48

Based on this approach, ‘travel’ characterizes the activities of ‘travellers’, or individuals “that move between different geographic locations for any purpose and any duration.”

‘Tourism’ is a subset of travel that characterizes the activities of ‘visitors’, who are a subset of travellers. specifically, a visitor is “a traveller taking a trip to a main destination outside his/her usual environment, for less than a year, for any main purpose (business, leisure or other personal purpose) other than to be employed by a resident entity in the country or place visited.” Trips taken by visitors are therefore referred to as ‘tourism trips’.

Furthermore, visitors are grouped into two categories: tourists and excursionists. A visitor is classified as a ‘tourist’ if their trip includes an overnight stay. Otherwise, they are classified as an excursionist, or a same-day visitor.

Based on these definitions, the UNWTO also describes different types of tourism activities:

Domestic tourism: activities of a resident visitor within the country of reference either as part of a domestic tourism trip or part of an outbound tourism trip

Inbound tourism: activities of a non-resident visitor within the country of reference on an inbound tourism trip

Outbound tourism: activities of a resident visitor outside the country of reference, either as part of an outbound tourism trip or as part of a domestic tourism trip

To operationalize the concept of the ‘usual environment’, contained within the definition a visitor, Canada qualifies a domestic trip as ‘touristic’ if it is an ‘out-of-town’ trip at least 40km one-way from the traveller’s home.49

Works Cited

- Ontario Ministry of Tourism. Culture and Sport (MTCS). 2014. The economic impact of tourism in Ontario and its regions 2000-2012. – unless otherwise stated

- MTCS. 2016. The economic impact of tourism in Ontario – 2013. http://www.mtc.gov.on.ca/en/research/econ_impact/econ_impact.shtml

- Ibid.

- OECD. 2016. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2016. OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/tour-2016-en

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 2015. UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2015 edition. http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284416899

- Ibid.

- UNWTO. 2016. World Tourism Barometer – Volume 15, May 2016. http://cf.cdn.unwto.org/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_barom16_03_may_excerpt_.pdf

- Tourism Industry Association of Canada (TIAC). 2015. Gateway to growth: annual report on Canadian tourism. http://tiac.travel/_Library/TIAC_Publications/New_ANNUAL_REPORT_EN.pdf

- Statistics Canada. Table 427-0004 – Number of international tourists entering or returning to Canada, by province of entry, monthly (persons), CANSIM (database). (accessed: June 29, 2016)

- MTCS 2014

- UNWTO 2015

- Krashinsky, S. 2016, July 7. With low dollar, tourism groups urge Canadians to consider ‘stay-cation’. The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/industry-news/marketing/with-low-dollar-tourism-groups-urge-canadians-to-consider-stay-cation/article30800101/

- Daniszewski, H. 2016, July 13. A break in gas prices spells a boost

for tourism in Ontario. The London Free Press. http://www.lfpress.com/2016/07/13/gasoline-prices-expected-to-remain-relatively-low-until-jan-1 - UNWTO. 2011. Tourism Towards 2030: global overview. http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284414024

- TIAC 2015

- OECD 2016

- TIAC 2015

- UNWTO 2016

- OECD 2016

- Ibid.

- Ontario Tourism Competitiveness Study. 2009. Discovering Ontario: a report on the future of tourism. http://www.mtc.gov.on.ca/en/publications/Discover_Ontario_en.pdf

- Tourism Industry Association of Ontario. 2014. Mapping Ontario’s tourism future: a five-year look back at the Ontario tourism competitiveness study.

- Ibid.

- New Zealand Ministry of Tourism. 2007. The Tourism Flows Model Summary Document. http://www.mbie.govt.nz/info-services/sectors-industries/tourism/tourism-research-data/other-research-and-reports/pdf-and-document-library/tourism-flows-model-summary.pdf

- TIAO 2014

- MTCS 2014

- Ontario Chamber of Commerce. 2016. Small Business: Too Big to Ignore.

- Industry Canada. 2015. SME Profile: Tourism Industries in Canada. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/eng/h_02951.html

- Ibid.

- Tourism HR Canada. 2015. The Future of Canada’s Tourism Sector: Shortages to Resurface as Labour Markets Tighten. http://cthrc.ca/en/research_publications/~/media/Files/CTHRC/Home/%20research_publications/labour_market_information/Supply_Demand/SupplyDemand_Report_Current_EN.ashx

- Industry Canada 2015

- MTCS. 2016. Ontario’s Tourism Action Plan. http://www.mtc.gov.on.ca/en/tourism/Tourism_Action_Plan_2016.pdf

- Ontario Tourism Education Corporation. 2012. Ontario Tourism Workforce Development Strategy 2012-17. http://www.otec.org/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=73ccfd09-50fd-419e-a9f9-365b570db7b8

- Tourism HR Canada 2015

- World Economic Forum. 2016. Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2015. http://reports.weforum.org/travel-and-tourism-competitiveness-report-2015/economies/#economy=CAN

- TIAC 2015

- Dachis, B. 2014. Full Throttle: Reforming Canada’s Aviation Policy. https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Commentary_398_0.pdf

- PwC. 2014. The Sharing Economy: How Will it Disrupt Your Business? http://pwc.blogs.com/files/sharing-economy-final_0814.pdf

- OECD 2016

- Ontario Chamber of Commerce. 2015. Harnessing the Power of the Sharing Economy. http://www.occ.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Harnessing-the-Power-of-the-Sharing-Economy.pdf

- Government of Ontario. 2016. Jobs for Today and Tomorrow: 2016 Ontario Budget. http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/budget/ontariobudgets/2016/

- National Airlines Council of Canada. 2014. The Economic Impacts of Proposed Increases to the Ontario Aviation Fuel Tax. http://airlinecouncil.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Lazar-fuel-tax-report_June-2014_final.pdf

- Government of British Columbia. 2016. B.C. Delivers on Commitment to Eliminate Jet Fuel Tax. https://news.gov.bc.ca/stories/bc-delivers-on-commitment-to-eliminate-jet-fuel-tax; Alberta Ministry of Finance. 2016. Taxes & Rebates. http://www.finance.alberta.ca/publications/tax_rebates/faqs_fuel-tax-act-budget-2015-change.html; Saskatchewan Ministry of Finance. 2016. Fuel Tax Programs. http://finance.gov.sk.ca/taxes/ft; Manitoba Finance. 2016. Fuel tax. https://www.gov.mb.ca/ finance/taxation/taxes/gasoline.html; Ontario Ministry of Finance. 2016. Gasoline Tax. http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/tax/gt/; Revenu Quebec. 2016. Fuel Tax Rates. http://www.revenuquebec.ca/en/entreprises/taxes/carburants/perceptiondeclaration/taux.aspx

- OECD 2016

- Ibid.

- Kirbyson, G. 2015. Grey Cup Fans Looking for a Place to Stay. Winnipeg Free Press. http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/grey-cup-fans-looking-for-a-place-to-stay-332609391.html

- Live Nation Entertainment. 2015. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fans-travel-to-and-from-the-show-like-rockstars-live-nation-and-uber-kick-off-marketing-partnership-with-venue-and-festival-focused-ride-program-300083343.html

- UNWTO. 2010. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/SeriesM/seriesm_83rev1e.pdf

- This definition excludes travel for certain activities, such as travelling to and from school or work, or moving to a new residence. See http://www.mtc.gov.on.ca/en/research/resources/Concepts_%20Definitions.pdf